When "computers" were women: from astronomy to ballistics and space travel

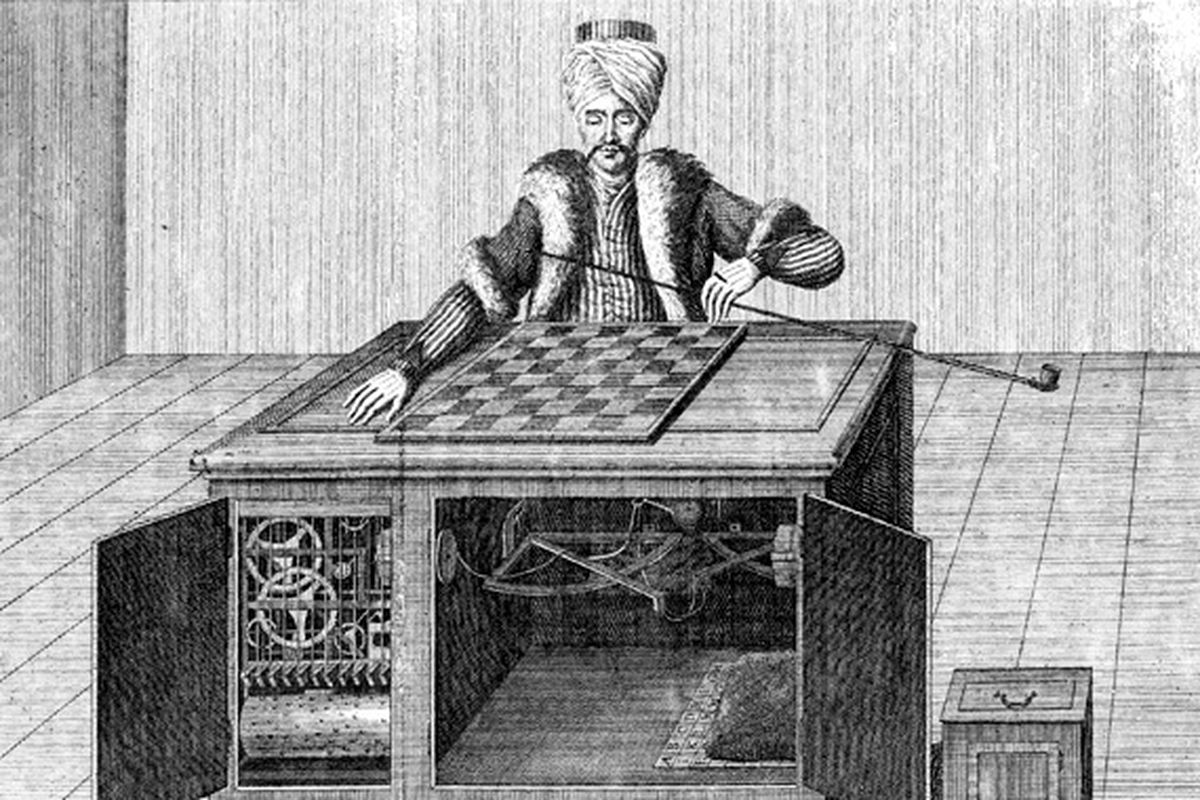

This is surprisingly not a very well-known dimension of the computing history. Before becoming the name of a machine, "computer" was actually a profession, that existed somewhere between the 1860s and the 1960s. Decades before actual computers came to be, "human computers" were mathematicians employed in cohorts by various institutions and companies to perform complex and repetitive calculations at a large scale.

Before computers were machines, they were people. They were men and women, young and old, well educated and common. They were the workers who convinced scientists that large-scale calculation had value. (...) They developed numerical methodologies and proved them on practical problems. These human computers were not savants, or calculating geniuses. Some knew little more than basic arithmetic. A few were near equals of the scientists they served and in a different time or place, they might have become practicing scientists had they not been barred from a scientific career by their class, their education, their gender or their ethnicity. - David Alan Grier (2001), in The Human Computer and the Birth of the Information Age.

Not all human computers were women, but a significant proportion of them were from the start, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, up until the end of the "human computers" era in the 1960s. Performing repetitive and complex calculations was considered at the time more of a clerical function with little to no prestige, and many directors employed women to save on wage's costs.

Men with mathematical abilities - while also composing a fraction of the human computer crowd - were more encouraged towards engineering positions, management roles or research direction. Women with mathematical qualifications, on the other hands, were having a harder time finding a suitable position (even when they managed to get a degree in the field). The increasing demand for human calculation until WW2 provided career paths for many women, hence a rather feminized profession. That was all before programming became a prestigious thing, and therefore a male-dominated industry later, in the 1970s and 1980s.

But let's get back to where heavy calculation needs emerged first.

"It all started with a comet": how astronomy became the first field to recruit human computers

Edmund Halley, a British astronomer and mathematician, had been told in 1681 by astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini about a theory stating that comets were objects in orbit. Halley made observations in September 1682 and used Newton's law of universal gravitation to compute the periodicity of what will become the Halley's Comet in his 1705 Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets. Yet, he quickly met overly complex obstacles in his calculations and left some to be addressed by the next generations.

When he attempted to compute the orbit of the comet that would eventually bear his name, he (Edmund Halley) realized that this orbit was influenced by the mutual interaction of the Sun, Saturn, and Jupiter. He struggled for many years to find a simple mathematical expression for this interaction, but ultimately failed. (...) He wrote in the final edition of his SYNOPSIS OF THE ASTRONOMY OF COMETS, “I shall leave them to be discussed by the care of posterity, after the truth is found out be the event.” - David Alan Grier (2001), in The Human Computer and the Birth of the Information Age.

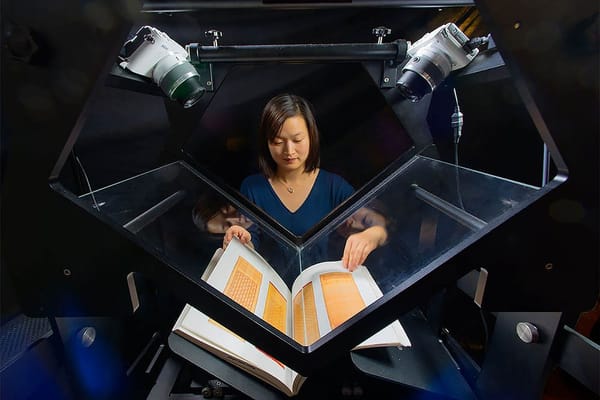

In 1758, French mathematician Alexis-Claude Clairaut took on the complex task of predicting Halley's Comet’s orbit. Working with astronomer Joseph Lalande and mathematician Nicole-Reine Lepaute, the team spent five months calculating by hand. Lepaute and Lalande focusing on the attraction of Jupiter and Saturn, while Clairaut calculated the orbit of the comet itself. Clairaut predicted the comet would reach its perihelion on April 13, 1759 — a remarkable achievement, even if off by 31 days. The idea of working with groups of "computers" and to divide labor by teams or people made its way through the astronomy scientific communities in the next decades. Several teams were assembled for specific projects in several research institutions in the world.

A century later, the Harvard Observatory hired young women as computers from 1876 onward. Under Edward Charles Pickering, nearly 80 women — sometimes dismissively called Pickering’s Harem — were tasked with analyzing stellar spectra and compiling what would become the Henry Draper Catalog, classifying over 10,000 stars. It's worth noting that Pickering’s motivations weren’t progressive: women were simply paid half as much as men. But their contributions became foundational to modern astronomy.

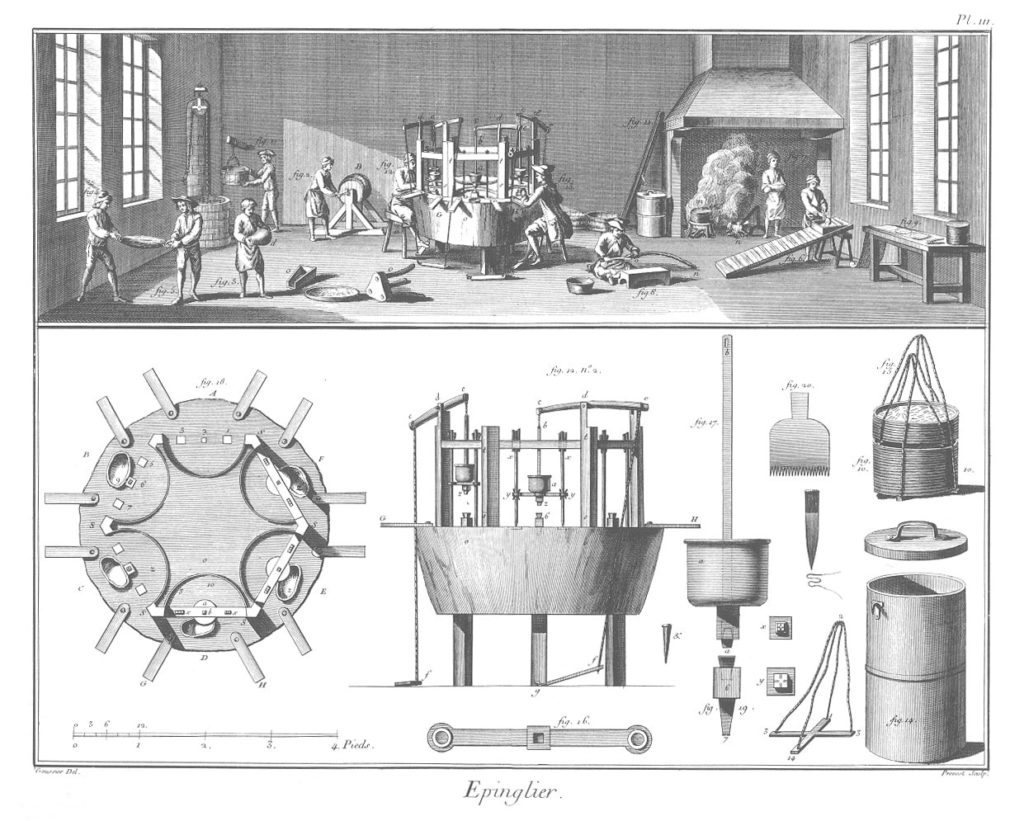

In France, the use of women in observatories was largely driven by economic concerns. During the massive international Carte du Ciel project launched in 1887 — which aimed to map the stars across 18 global observatories — the sheer volume of measurements and calculations overwhelmed astronomers. To meet the demand, the Paris Observatory created a women’s computing workshop in 1892, led by Dorothea Klumpke, the first woman to earn a doctorate in astronomy. The team thus created was called "Les dames de la carte du ciel" (The ladies of the sky chart). The Toulouse Observatory followed in 1895, adopting an industrial model: female calculators worked from home or on site, under male supervisors, with pay based on the complexity of the task — from 0.01 francs per hour for additions to 0.60 francs for multiplications.

These women were low-paid, flexible labor, hired by the hour or day, with no job security and little room for advancement.

Then came the World Wars...

During World War I, demand for human computers surged — especially for navigation and artillery tables. With men at the front, many of the new recruits were educated women, stepping in to meet the need.

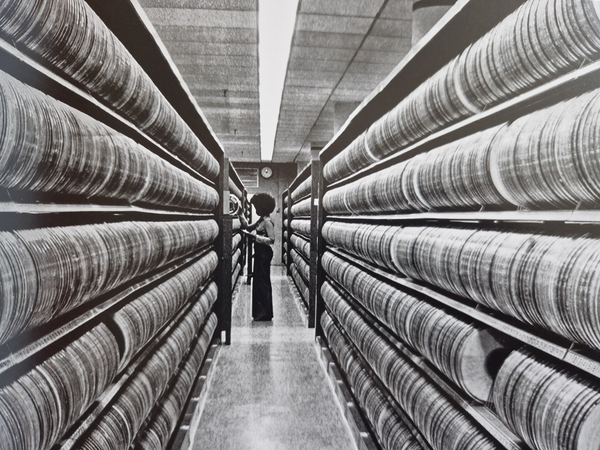

With the rapid evolution of warfare, anti-aircraft trajectory calculations became a priority. In the U.S., the military recruited human computers for ballistic work: about 60 men at Aberdeen Proving Ground and a smaller mixed-gender team in Washington, D.C. focused on projectile range tables.

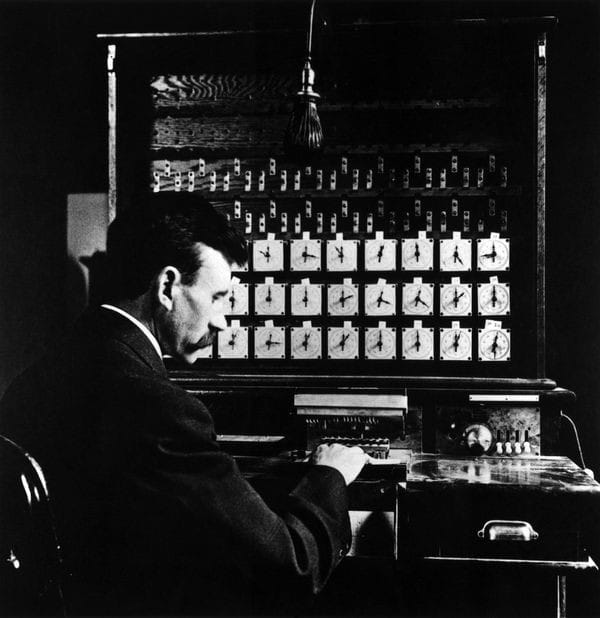

One key figure of that time was Gertrude Blanch (1898–1996), a Poland-born mathematician who led one of the largest pre-digital computing teams as part of the "Mathematical Tables Project", funded by the WPA during the Great Depression. The project employed over 450 workers, many untrained or unemployed, to produce mathematical tables for functions like logarithms, exponentials, and trigonometry. This project latter became the Computation Laboratory of the National Bureau of Standards.

Blanch organized the work much like an industrial assembly line: some workers handled additions, others subtractions, and a smaller group multiplications — all carried out at long rows of desks in a New York warehouse. By 1942, the team was redirected to support the war effort, with Blanch overseeing military computations for the army, navy, and beyond.

After World War I, the field of human computing became more structured and professionalized, especially in the U.S. During World War II, demand for computation exploded—from ballistic trajectories and shockwave propagation to navigation tables and code breaking. A labor shortage meant women entered the field in large numbers. As historian David Grier puts it:

“Some time in 1944, computers became girls.”

At Bell Labs, George Stibitz, a pioneer of early digital computing, reportedly began estimating project timelines in “girl-years” of effort. One member of the military’s Applied Mathematics Panel even coined the unit “kilogirl”, referring to a thousand hours of female computation work. But even then, computing wasn't just women's work—it was the work of the dispossessed: women, African Americans, Irish immigrants, people with disabilities, and the working poor. It was the only door open for many without access to elite scientific careers.

It's worth mentioning that human computers also contributed to other significant projects, including the Manhattan Project to build the first nuclear weapons, but also in fields like medical research, meteorology, radiation and particle research.

Beyond the military: human computers in the field of spatial exploration

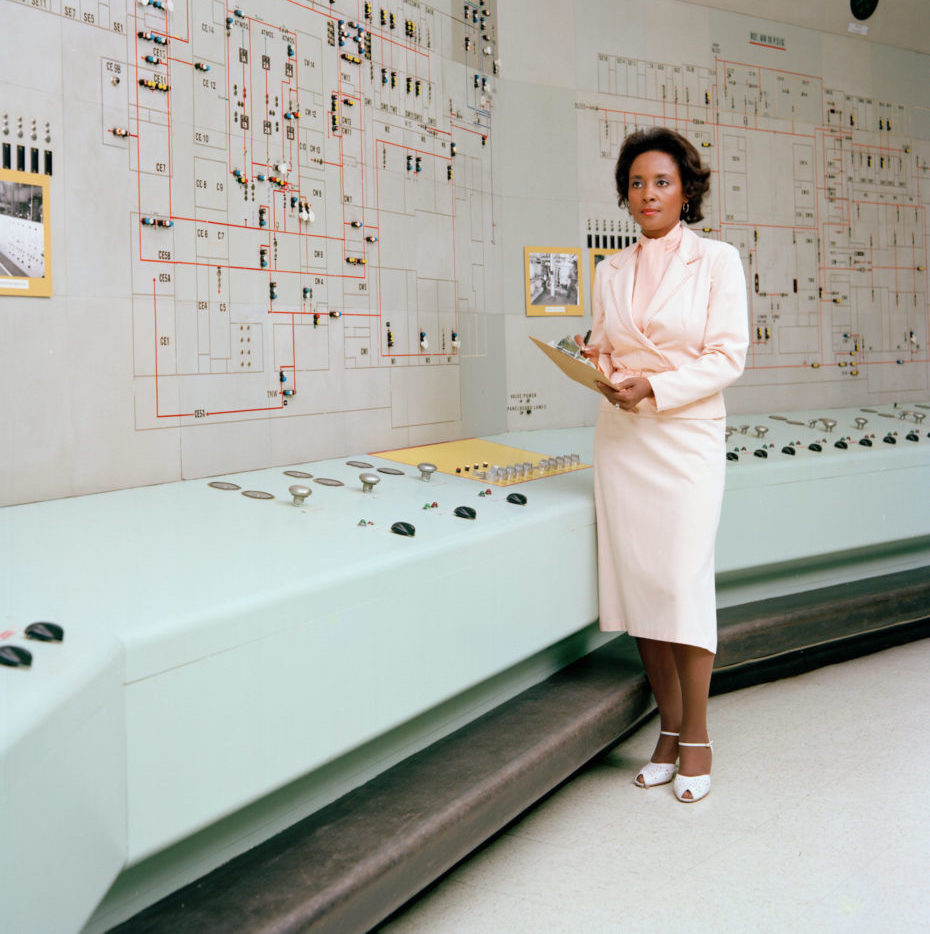

Women computers also played a central role in aeronautics and early space research, particularly at Langley Research Center, the largest facility of the NACA (NASA’s predecessor). Teams of female computers—educated and highly skilled—carried out critical calculations.

By the 1940s, Langley began hiring African American women with college degrees, who worked in a segregated section called the West Area. Their story was later brought to light in the film Hidden Figures (which I strongly recommend watching).

From calculations to computer programming

Most of the earliest programmers in the world were actually human computers who were asked to take care of the new, gigantic machines that started entering institutions in the post-war years (which ultimately killed the profession).

During the war, 200 women were also recruited at Aberdeen Proving Ground to manually compute firing tables for artillery shells and other projectiles. These tables helped soldiers aim accurately, and required complex and time-consuming calculations. Producing just one firing table could take a full month of work by a team of 100 women.

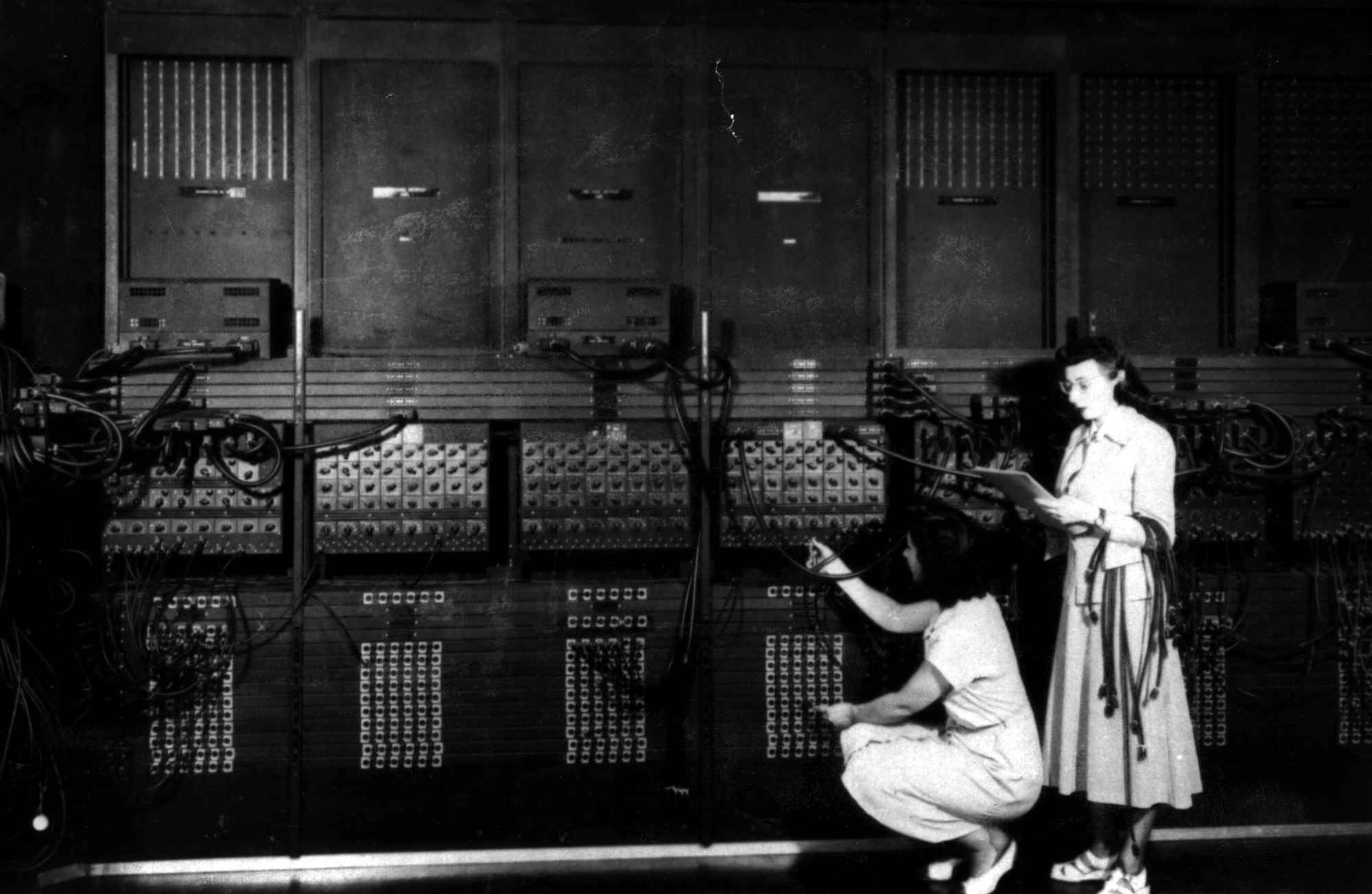

It was from this talented group that six women were selected in June 1945 to secretly operate the ENIAC, the world’s first fully electronic and programmable computer.

Built at the University of Pennsylvania starting in 1943 and completed in late 1945, the ENIAC was designed specifically to accelerate ballistic calculations. The women who programmed this 30-ton machine were Kathleen McNulty, Frances Bilas, Betty Jean Jennings, Elizabeth Snyder Holberton, Ruth Lichterman, and Marlyn Wescoff—now collectively known as the ENIAC Girls. Today, they’re recognized as some of the world’s first computer programmers, though in the 1940s, they were simply called coders.

Similarly, in the movie Hidden Figures mentioned above, we see one of the main characters, Dorothy Vaughan, having to steal from the library a FORTRAN guide. Dorothy Vaughan has learned that NASA has installed an IBM electronic computer, and she realizes that this machine threatens to replace “human computers,” particularly the West Area Computer division of Black women computers she supervises.

Dorothy Vaughan played a key role in preparing her colleagues for the shift from human to electronic computing at NASA. She taught herself the programming language FORTRAN and passed on her knowledge to others, including future space pioneers. She remained at NASA-Langley for 28 years.

Many other women computers made the critical leap from human computing to early programming. At the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), women like Barbara Paulson transitioned from calculating rocket trajectories by hand to writing code for early space missions. Similarly, women working as astronomical computers at Harvard Observatory—such as Annie Jump Cannon and Henrietta Swan Leavitt—paved the way for computational methods in astrophysics, with some adapting to machine-based analysis as technology evolved. Within NASA, alongside Vaughan, both Mary Jackson and Katherine Johnson became key figures in programming and engineering during the space race.

Additional sources

- The book "When Computers Were Human" by David Alan Grier (2005), Princeton University Press.