Tim Berners-Lee, the CERN, and the invention of the World Wide Web (1989)

This story marks one of the most important moments in the history of computing. Tim Berners-Lee's invention was so revolutionary that it spread across the globe within a few years, transforming how human civilization communicates and manages information through the use of hypertext. The creation of the World Wide Web is widely seen as a historical turning point—often compared in significance to Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the 15th century.

To me, it was just something that grew as the same time as I did, allowing me to build my first blog in 1994 (spoiler, it was about horses), becoming a place to explore what felt like a limitless universe, meet with strangers online, build community, play video games, escape the emptiness of my parents suburban home and lifestyle. The Web has enabled me (and most of my generation, as much as the following) to get empowered and to expand our horizons way beyond geographical boundaries. It has - even now - enabled my entire technical documentation career as much as my passion to write and research, to structure and link information.

To understand the context of the Web’s invention, it’s important to make a key distinction: the Internet already existed before the World Wide Web. In fact, the Web could not have existed without the Internet, as it depends on its underlying infrastructure to function.

Let’s begin there—by exploring what the Internet is, and how it came to be.

What is the Internet?

The Internet is the technical and physical infrastructure that enables the Web. It existed before the Web was invented. The context for the invention of the Internet emerged mainly from the combination of four things:

(1) Military motivations

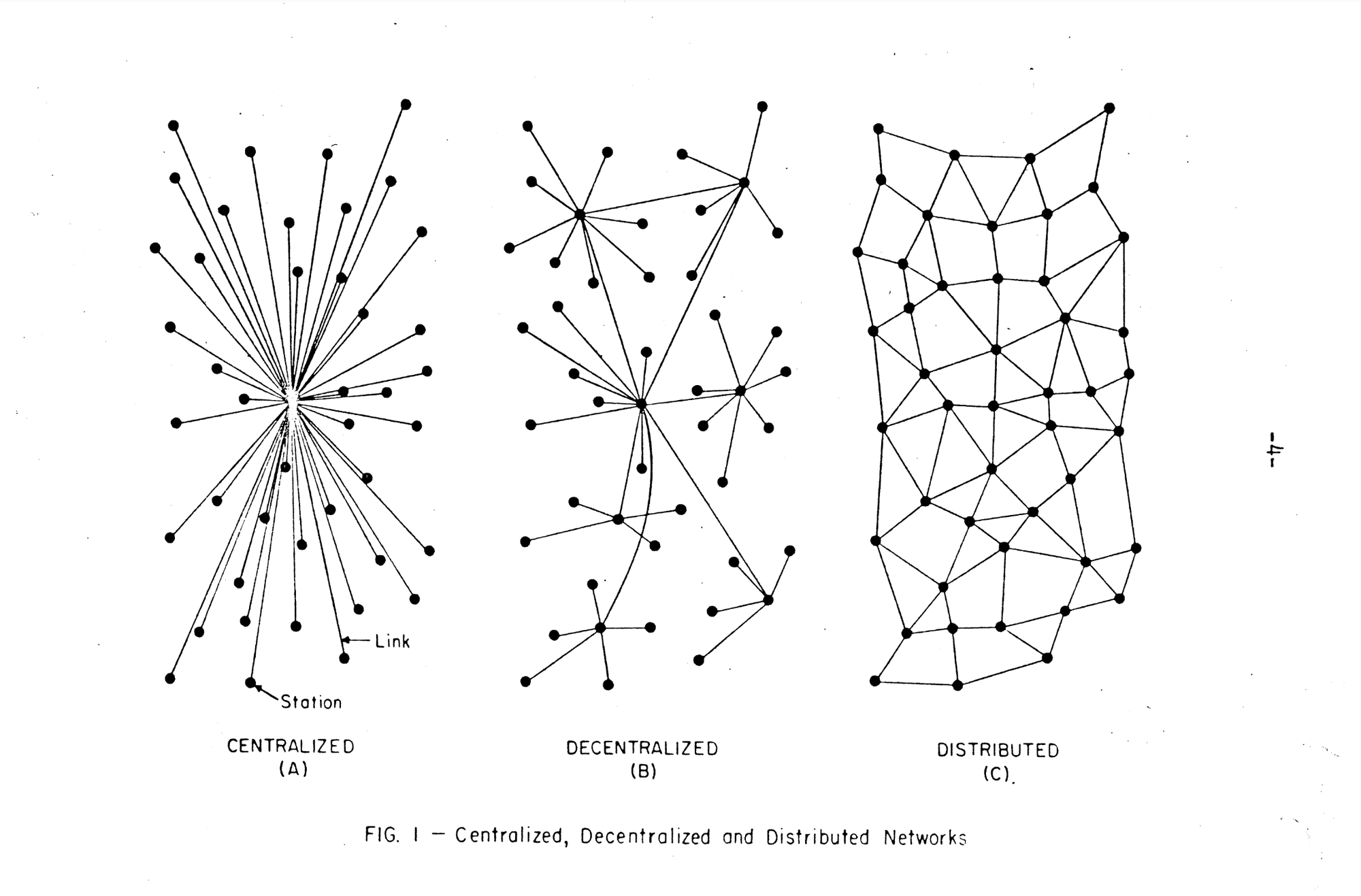

First was the will (from the military and US government) in the 1960s to create a network of computers connected together beyond one institution or one place, that could basically resist a nuclear attack. The idea was to preserve the capacity to communicate and exchange information in case of major crisis, under a principle of survivability. This principle was defined by engineer Paul Baran and mentioned in a report in 1962, named "On Distributed Communication Networks":

This communication network shall be composed of several hundreds station which must intercommunicate with one another. Survivability as herein defined is the percentage of stations surviving a physical attack and remaining in electrical connection with the largest single group of surviving stations. - Paul Baron, 1962.

(2) Switching packets

Second, came the invention of packet switching networks by engineer Paul Baran in the US (author of the report mentioned above), and physicist Donald Davies in the UK. This technology revolutionized digital communication by dividing data into small packets that travel independently across a shared network, allowing for efficient bandwidth use, resilience to failures, and scalable, decentralized growth.

(3) The TCP/IP protocol

Third came the invention of the TCP/IP protocol, that stands for Transmission Control Protocol / Internet Protocol, by Robert Elliot Kahn and Vint Cerf. TCP/IP is a suite of communication protocols developed in the 1970s to enable reliable data exchange between computers on different networks. IP handles addressing and routing: it ensures that each data packet finds its way to the correct destination. TCP, on the other hand, ensures that these packets arrive intact and in order, providing mechanisms for error checking, retransmission, and data integrity.

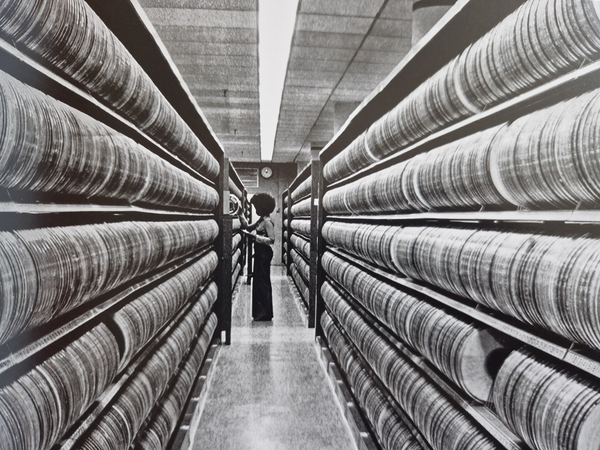

(4) The Hypertext

Fourth was the invention of hypertext. Hypertext is the idea of linking pieces of information across documents. It was first imagined in the 1940s by Vannevar Bush with his Memex concept, a theoretical machine that would let users "trail" their thoughts through linked microfilm. In the 1960s, Ted Nelson coined the term "hypertext" and worked on Project Xanadu, aiming to build a universal, non-linear writing system. Around the same time, Douglas Engelbart developed NLS, an early hypertext system that also introduced the mouse and collaborative editing. We have a full article dedicated to Douglas Engelbart's work and legendary "mother of all demos".

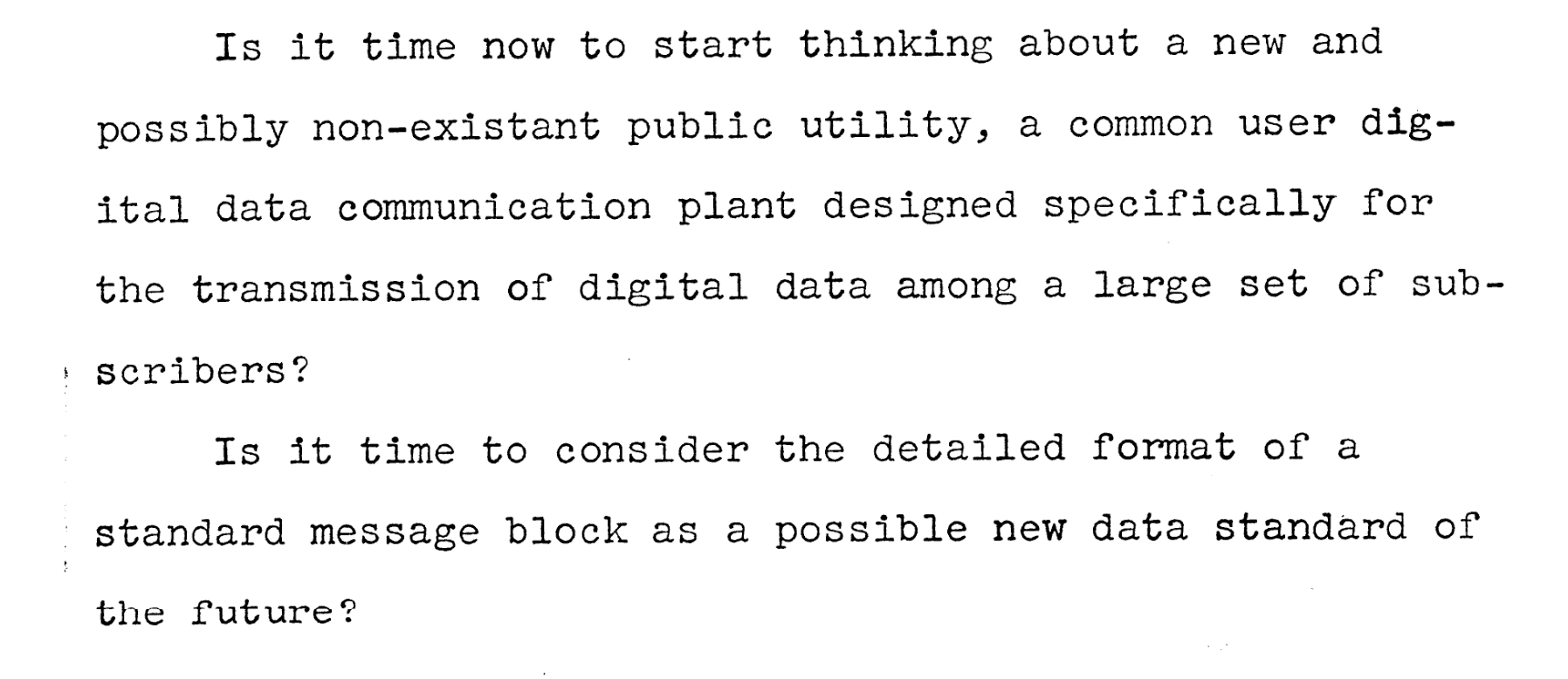

The combination of those visionary projects laid the groundwork for the World Wide Web to become possible. As Baran stated at the end of his 1962 report for the RAND corporation:

A collective endavour

As always, when it comes to innovation, it's never about one single person coming up with a magical solution from nothing. Technological innovations emerge from collectives of people working on concrete problems in institutions for a long time (most of the time scientific institutions, on public funds), in a collaborative and iterative manner, feeding on each other's work. Once systems and concepts have diffused at a wide enough scale, then new innovations can emerge and diffuse, enabling another layer of innovations to come. That is exactly what happened in the history of the Internet, and the Web.

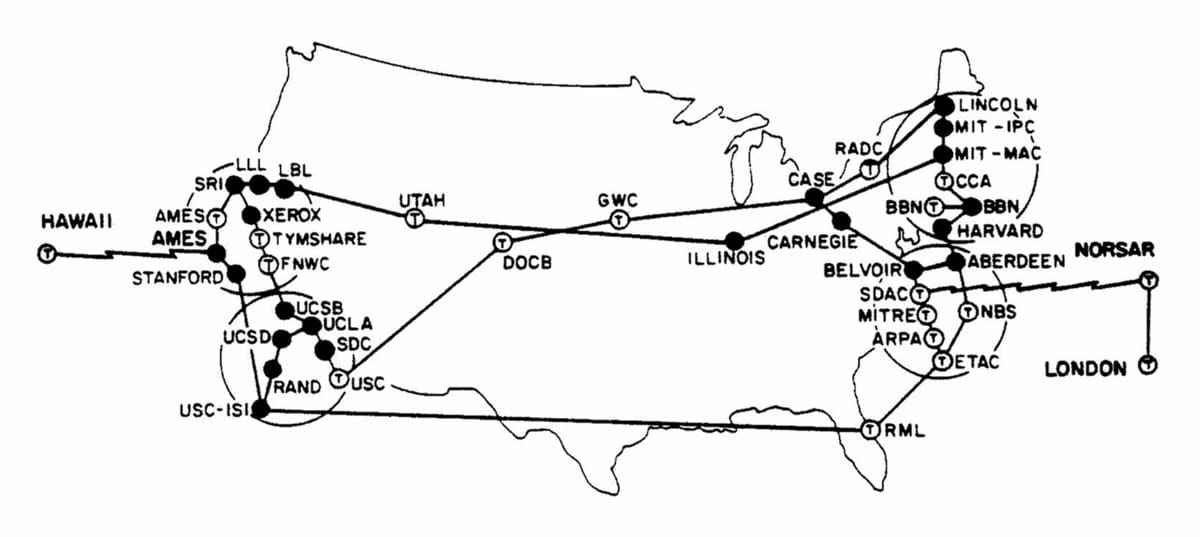

The ARPANET, for Advanced Research Projects Agency Network, was established by the Advanced Research Projects Agency (now DARPA) of the United States Department of Defense. It was primarily used by researchers, scientists, and academic institutions funded by the U.S. Department of Defense to share computing resources, collaborate on projects, and exchange electronic messages. Its early users at institutions like UCLA, SRI, and MIT utilized it for remote login (Telnet), file transfers (FTP), and the early form of email—which rapidly became its most popular application.

By 1989 - the year Tim Berners-Lee had the idea for the World Wide Web - the Internet had already matured into a robust network of networks, primarily serving academic, military, and research institutions. Users accessed remote systems via tools like Telnet, transferred files with FTP, and exchanged messages via email and Usenet newsgroups. Computers had gained graphic interfaces and word processor software (as demonstrated by Douglas Engelbart in 1968), and started to be more extensively used among scientists and specialists.

However, the Internet lacked a unified, user-friendly way to navigate or hyperlink documents. Its interface was largely command-line driven and text-based, so not very accessible to the non-specialists.

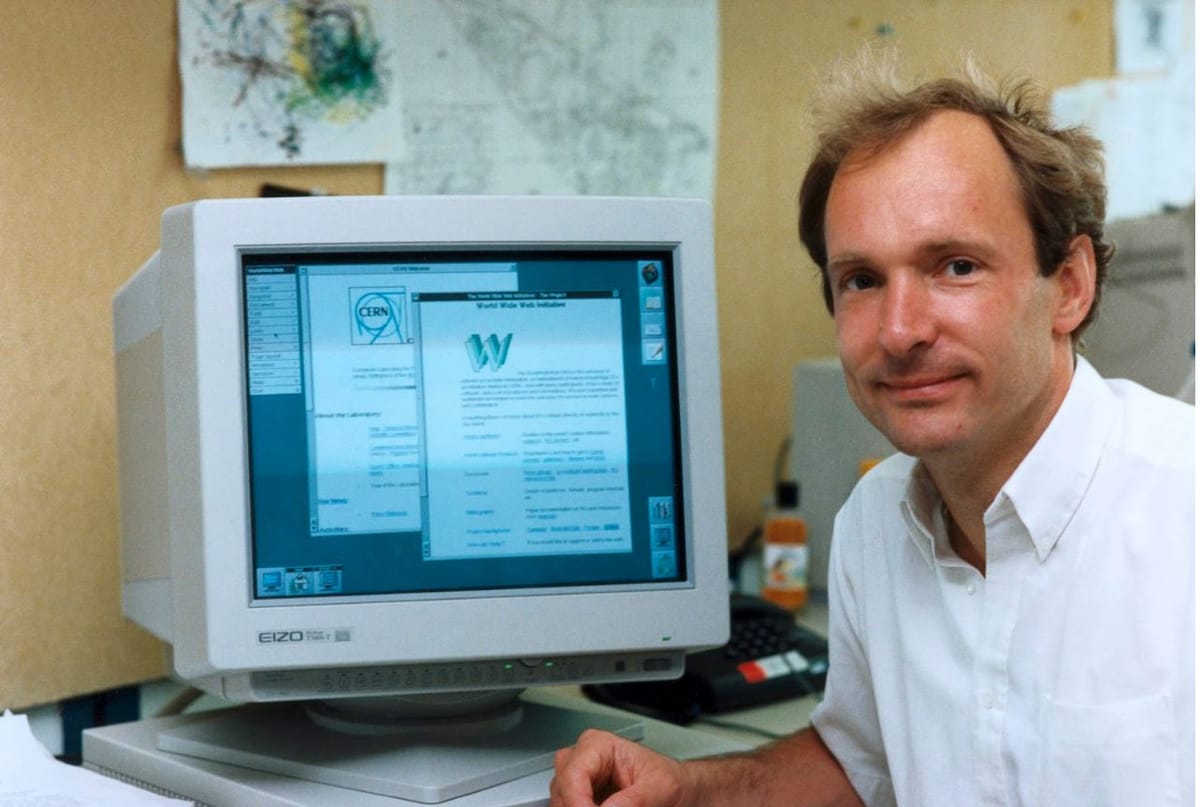

Tim Berners-Lee and the CERN

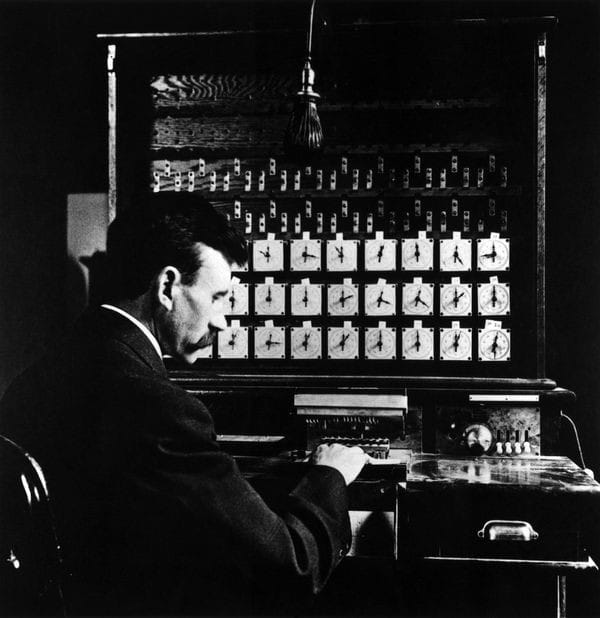

Tim Berners-Lee was born and raised in London. Both his parents were mathematicians and computer scientists, and they worked on the world's first commercially available digital computer: the Ferranti Mark 1 at the University of Manchester. Tim Berners-Lee graduated from Oxford in physics in the 1970s and started an engineering career working in telecommunications and software.

ENQUIRE: the first step

In 1980, Berners-Lee was hired as a contractor at CERN in Geneva. At that time, CERN had a workforce of about 10,000 people, all using different hardware, software, and systems to manage their work. It was also the largest Internet node in Europe. Scientists relied heavily on email and file exchanges to coordinate overlapping research projects — a process that was often chaotic and hard to scale.

Berners-Lee built a personal tool called ENQUIRE to help organize information more effectively. There was a major challenge: any new system had to work across a jumble of incompatible networks, disk formats, data structures, and character encodings. Transferring information between these disjointed systems was usually more trouble than it was worth.

Earlier hypertext systems like Memex and NLS existed, but they didn’t meet these interoperability demands — ENQUIRE was an attempt to solve that.

Inventing the World Wide Web... out of "desperation"

Creating the web was really an act of desperation, because the situation without it was very difficult when I was working at CERN later. Most of the technology involved in the web, like the hypertext, like the Internet, multifont text objects, had all been designed already. I just had to put them together. It was a step of generalising, going to a higher level of abstraction, thinking about all the documentation systems out there as being possibly part of a larger imaginary documentation system.

— Tim Berners-Lee (source)

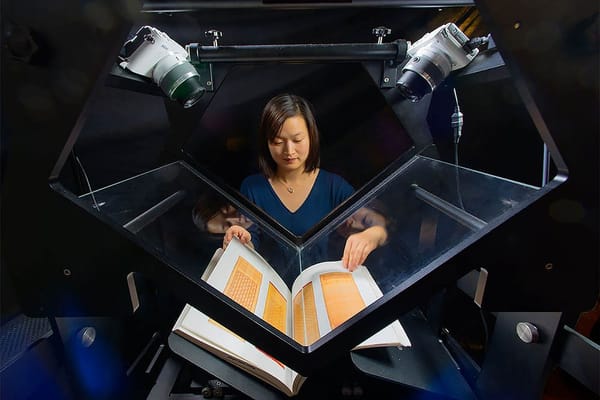

The early days of personal computing (graphic interface, word processor) and the frustration of having scattered resources to be accessed by different systems (T. Berners-Lee, 2007)

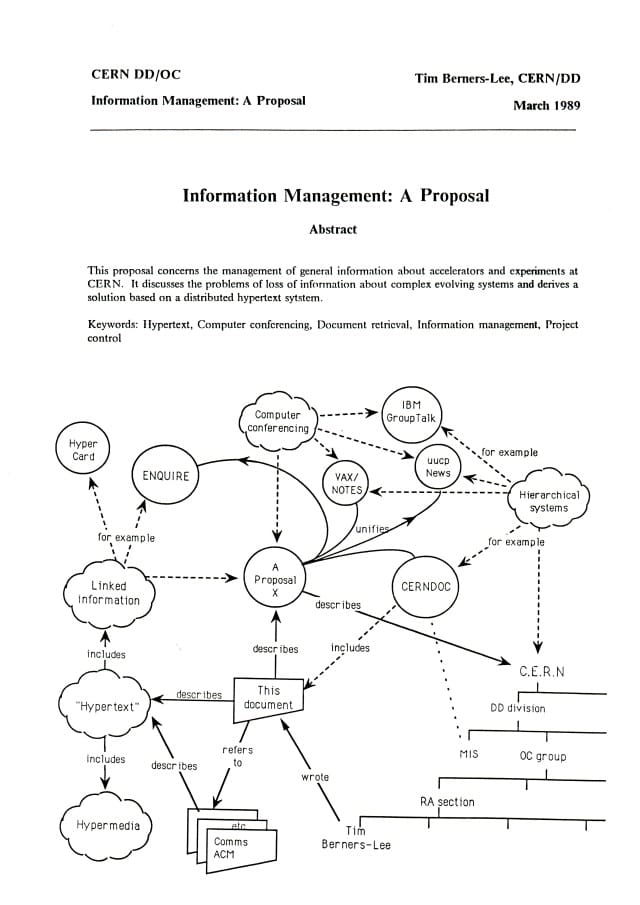

After the first ENQUIRE attempt, Berners-Lee then left to go work for another company, and got back to CERN in 1984. Building on his initial project to allow for scientists and students to collaborate more easily on projects, Berners-Lee pushed his idea to build a system that would associate the Hypertext with the Internet. He received little enthusiasm at first. Below is the proposal for information management he shared in 1989.

This was the blueprint for a system that would use hypertext to link documents across a distributed network. To make this system work, Berners-Lee developed three key technologies:

- URL (Uniform Resource Locator) – the address system for identifying resources on the web (like

http://example.com). It told browsers where to find things. - HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) – the set of rules that defined how browsers and servers communicate. It allowed users to request and receive documents over the Internet.

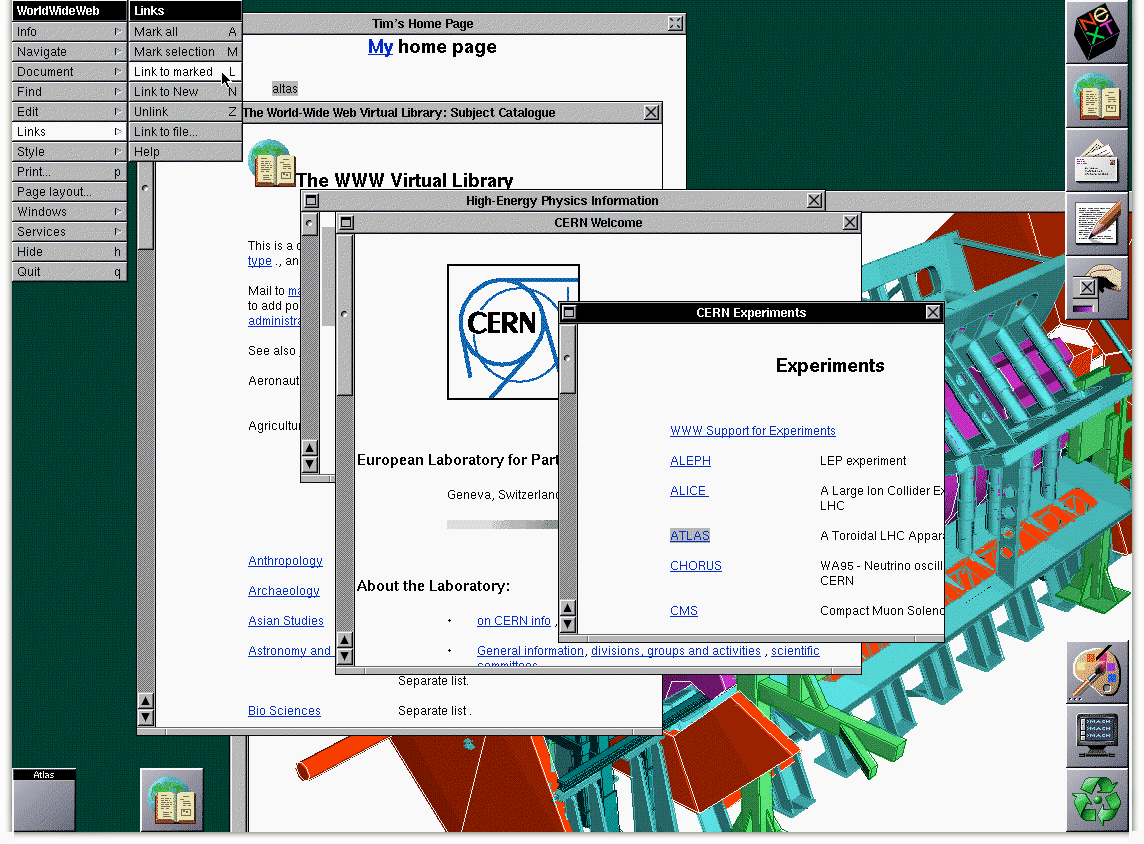

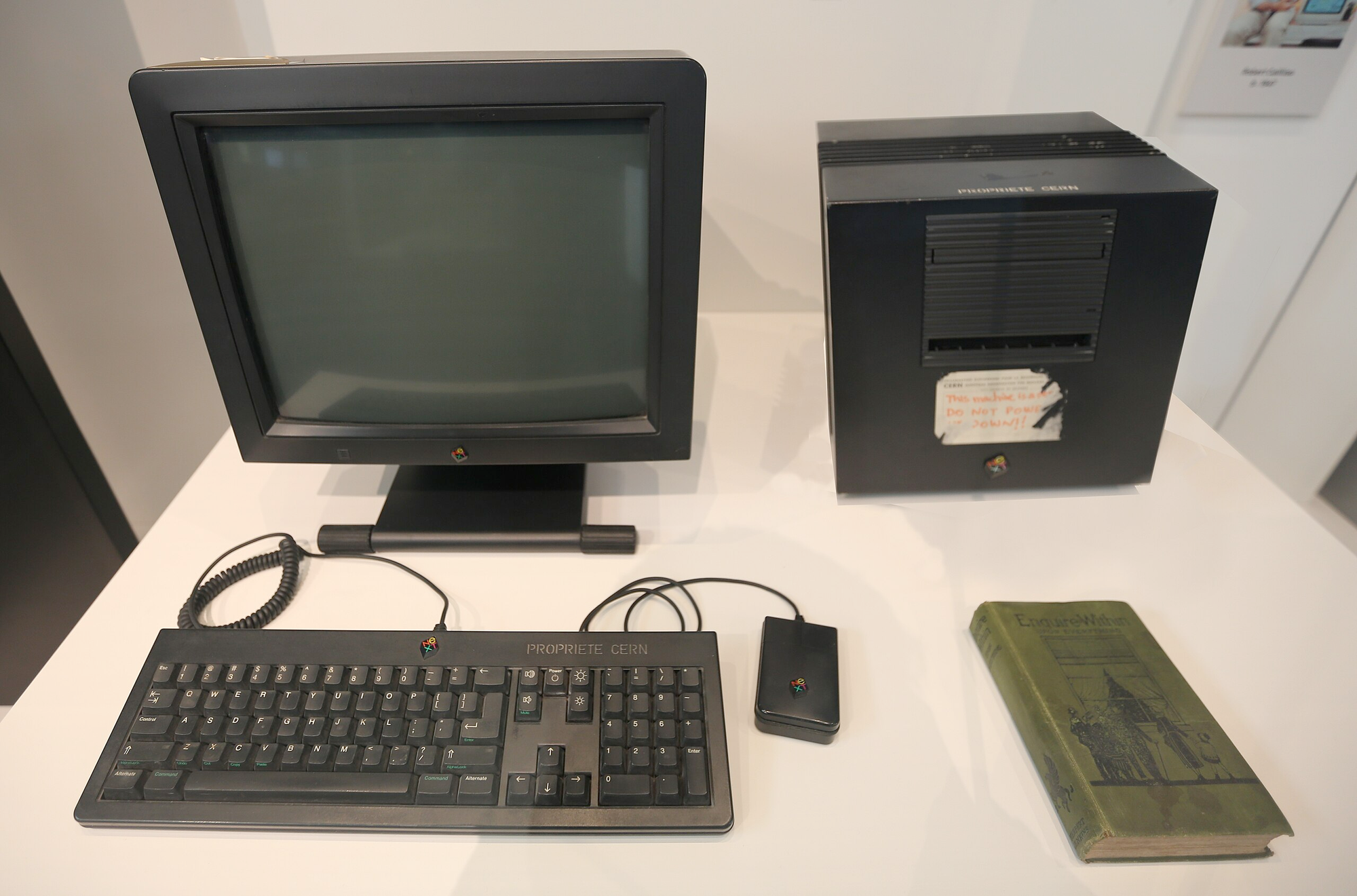

- In 1990, he built the first web browser (called WorldWideWeb, later renamed Nexus) and the first web server (running on a NeXT computer at CERN).

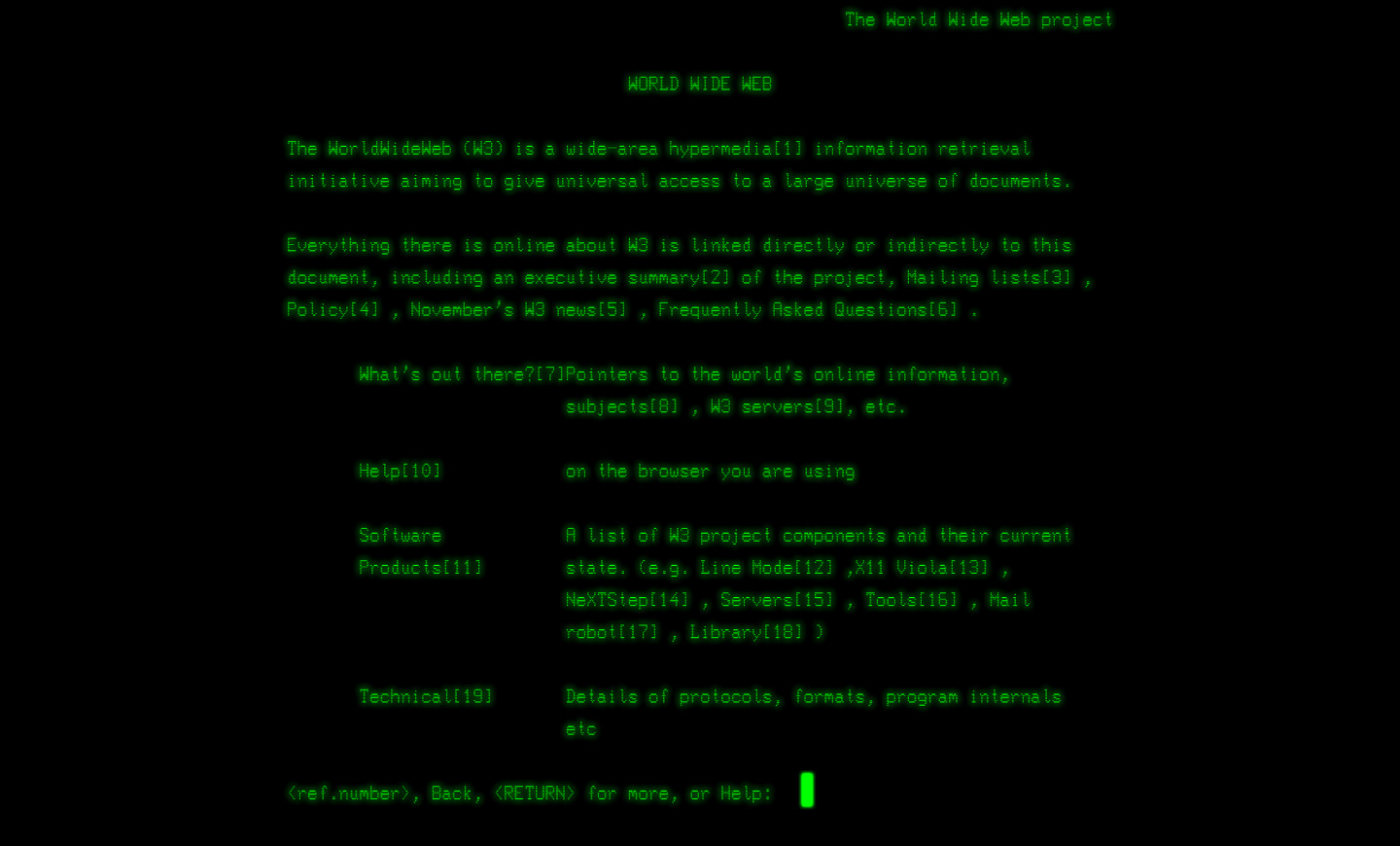

The first website went live in 1991, explaining the project and how others could set up their own servers.

At first, the system was used internally at CERN, but Berners-Lee was a strong believer in openness. In 1993, CERN announced that the web's underlying code would be released into the public domain with no patents, and no fees. This move was revolutionary. It allowed developers and institutions around the world to build their own websites and browsers, leading to the explosive growth of the web in the mid-1990s.

Global diffusion

It only took a couple of years between Berners-Lee proposal and the beginnings of the global diffusion of the WWW. In December 1991, the first web server in the United States was set up at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC), following earlier developments at CERN. At the time, only two types of browsers existed: a complex one for NeXT machines and a simpler line-mode browser for broader compatibility. As the system needed wider development, Tim Berners-Lee invited external programmers to contribute. This led to new browsers like MIDAS, Viola, and Erwise.

In early 1993, the NCSA (National Center for Supercomputing Applications) released the Mosaic browser, which introduced a graphical interface and was later made available for PC and Macintosh. This significantly accelerated the Web’s adoption.

Since the early 1990s, Tim Berners-Lee has consistently advocated for an open, accessible, and decentralized Web, a battle that many declare now lost to the big corporations, GAFAM and capitalistic greed.

Nevertheless, Berners-Lee has emphasized that the Web should remain a universal platform—free from corporate control, censorship, and fragmentation. To support this vision, he helped establish the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) in 1994, an international body that develops open standards to ensure the long-term growth and interoperability of the Web. Through the W3C and later initiatives like the Web Foundation and Solid project, Berners-Lee has continued to promote web standards, user privacy, and data ownership as core principles of the Web’s future.

www. subdomain (short for World Wide Web) to indicate that this was their web interface. It helped distinguish the web server from other services on the same domain, like ftp.example.com or mail.example.com. Today, the www has become optional, but the http protocol Berners-Lee conceptualized is still in place, hence every single URL on the web starting with http:// (and now, https, which is a more secure version).By expanding the volume of information accessible and "browsable" through hyperlinks (and later, browsers and search engines), the inventors of the Internet and the Web provoked a qualitative shift in how human societies operate. A shift that has led to (or accelerated greatly) the "digitalization" of society, from medical files to online advertising, to how governments allocate budgets, conduct wars, how corporate businesses and financial institutions operate, how science is being produced, how media work, and how we see and present ourselves to the world, from social media profiles to personal online records.

We will dive deeper into those later aspects of the web in other pieces, as there is - of course - much to say.

"The great triumph of the Internet Era is that we connected all the computers in the world together, and thereby set out to map and encode all of human thought. The fact that humans can access their own collective knowledge is because the hyperlink strings it all together in the same way our brains are wired. The hyperlink brings software concepts to text and the structure of the humain brain to digital data. It is a conceptual melding in both directions"

- Brian McCullough (in Torie Bosch Ed., 2022, p. 84)