The Wonderful World of Tape Libraries: Data Storage in the Mainframe Age

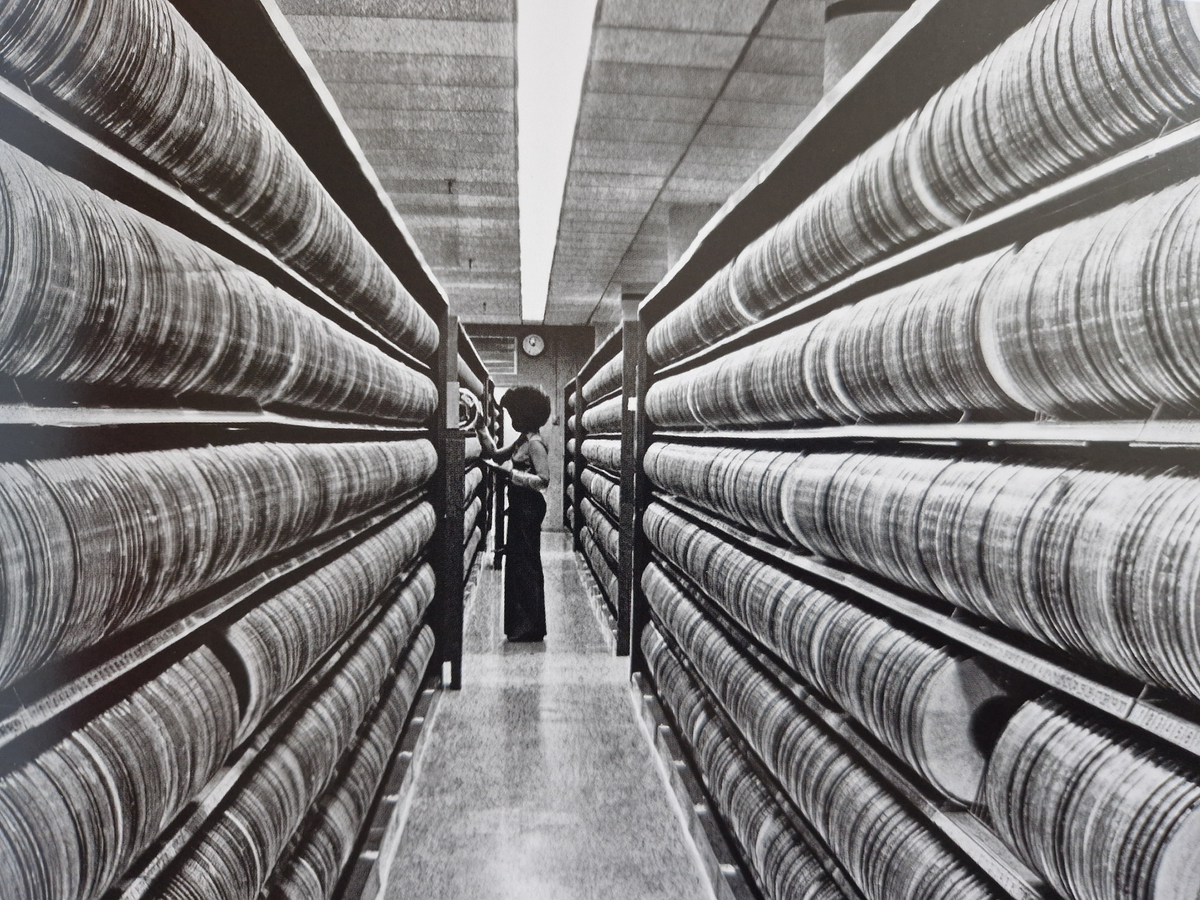

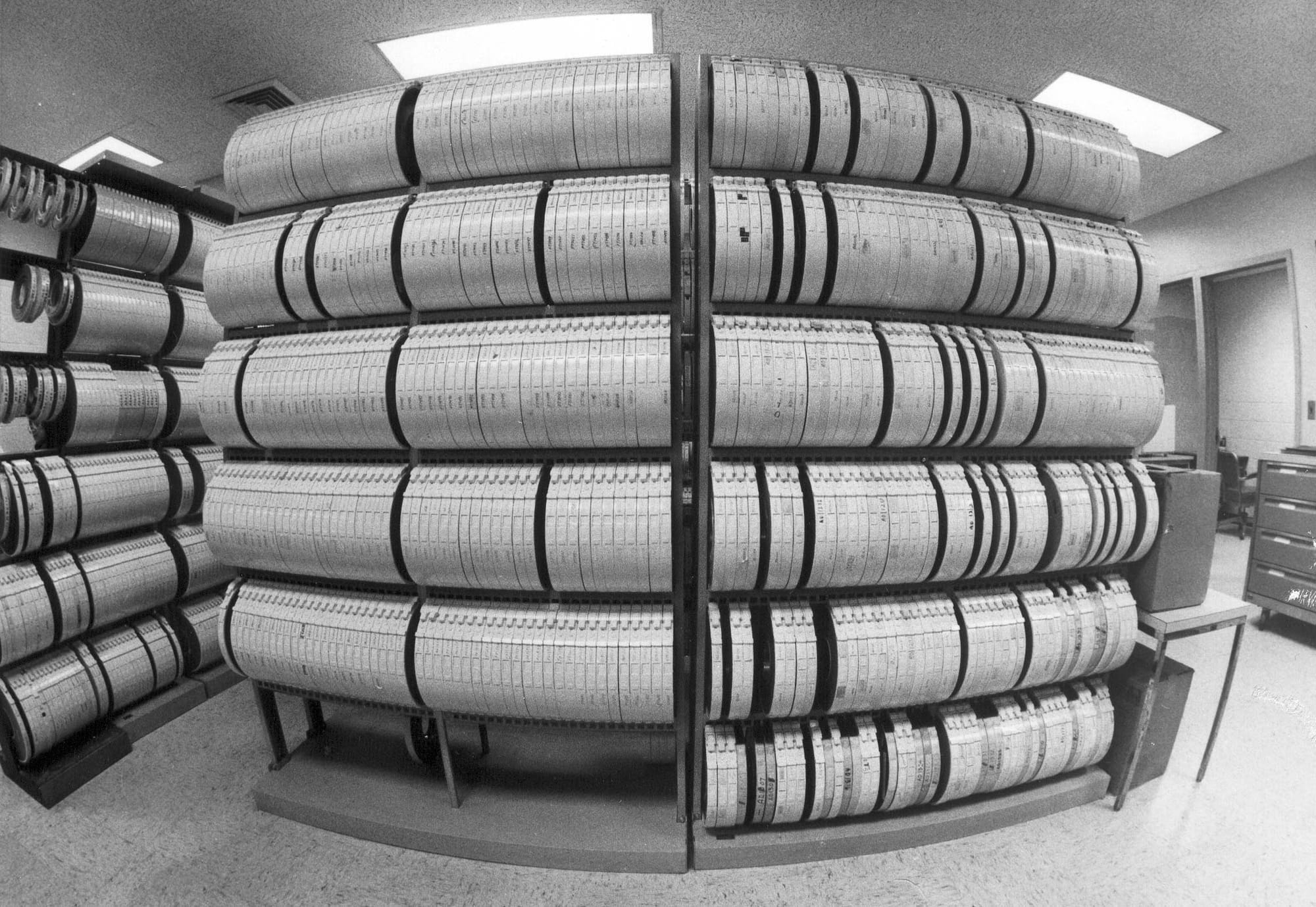

Imagine rooms and corridors filled up not with books, but with reels of magnetic-tapes. Thousands and thousands of magnetic tapes stocked in their cases, stacked on shelves, over kilometers of corridors, meticulously numbered and ordered.

In the middle of the room, a cartwheel or two, needed by the librarian to get batches of reels and transport them to the computer room, and then back to the library.

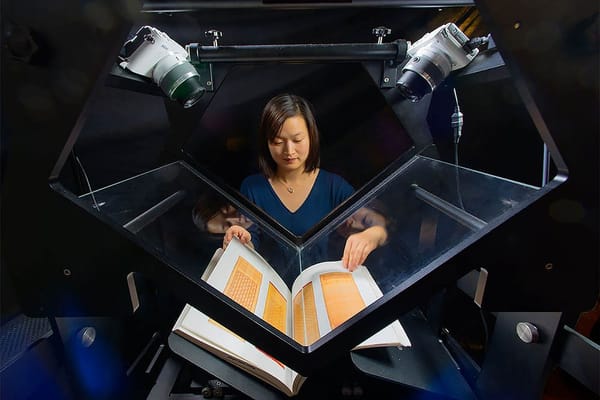

Those special places were called tape libraries, and were iconic elements of the mainframe age between 1945 and the early 1980s. Every big institution or research facility using IBM mainframes to perform computation and handle large amount of data was equipped with tape libraries. The machine and the data were physically separated at the time: people needed to literally go to the next room, fetch a set of raw data recorded on a tape, then bring that data physically to the computer, and remove it after the computation was done to return it to storage for further use.

Tape libraries and mainframe computers required a tremendous amount of manual labor. Tapes had to be correctly labelled, filed, and located. Tape operators — sometimes called librarians — worked among the towering shelves, fetching reels, cleaning drives, and maintaining the rhythm of the organization’s memory. Later, the physical handling of magnetic tapes was automatized both with software and hardware (now handled by robotic installations), and the noble profession of tape librarian as here described disappeared. But at the time, keeping track of the whereabouts of the tapes was a formidable and high-responsibility job, essential to for the operations to run smoothly and for the data to be preserved safely.

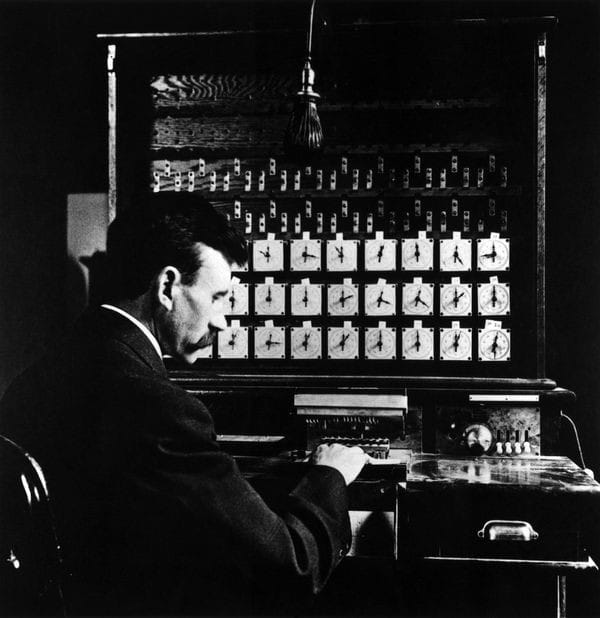

The constraints of batch processing

Rather than interactive computing, the dominant method at the time was batch processing. This meant that data wasn’t worked on in real time, but processed in large, scheduled jobs that ran overnight or during low-usage hours.

The system would process both tapes, merge the old data with the new, and write the result to a fresh reel — a newly updated master file. That new reel would then be stored until the next update cycle. Often, earlier versions were kept as well, just in case errors were discovered, and the entire process needed to be redone. This kind of rollback safety was critical in an era where re-running a job meant physically finding and remounting the right tapes.

Research institutions like NASA, scientific research centers, medical research institutes, universities, but also administrations like Census bureaus, social security administration, health and tax services and private businesses had their own tape libraries, and associated librarians.

Tape libraries today

Some institutions like CERN, NASA and almost all the big private companies and big cloud providers like Microsoft Azure operating today rely on tape libraries to store massive amount of data. This is rarely known and advertised to the public, but magnetic tape storage - now fully automatized - is a cheap (a few cents per gigabyte), reliable (typical storage duration is 30+ years versus 5 years for a disk or hard drive) and secure (as it is fully offline, data are protected from cyberattacks and data thief) system to preserve petabytes of data.

Modern days tape libraries have sadly lost the vintage charm of the mainframe era, as they are fully automatized machines managed remotely by pieces of software and robot arms. They remain a low-cost, high efficiency storage method, more sustainable and less energy-consuming than traditional data centers and drives.

Additional sources

--> Columbia University tape library archive: https://www.columbia.edu/cu/computinghistory/tapes.html