Long Before the Internet: The Telegraph Submarine Cable Network (1850 - 1950)

Inventing the Telegraph

I didn’t suspect—until recently—that submarine cables existed long before the Internet and fiber optics were invented. I had always assumed we waited until the invention of the telephone to start laying thousands of kilometers of copper cables across the ocean floor to transmit information between continents.

But then I discovered that the earliest submarine communication cables were actually linked to another great invention: the telegraph. I had assumed that this method of communication, using Morse code, was so ancient that it would be anachronistic to associate it with undersea cables—but in fact, the very first attempts to span oceans with cable were made for the telegraph as early as 1851.

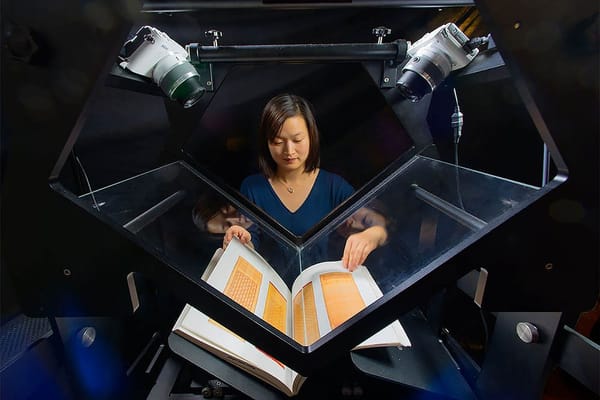

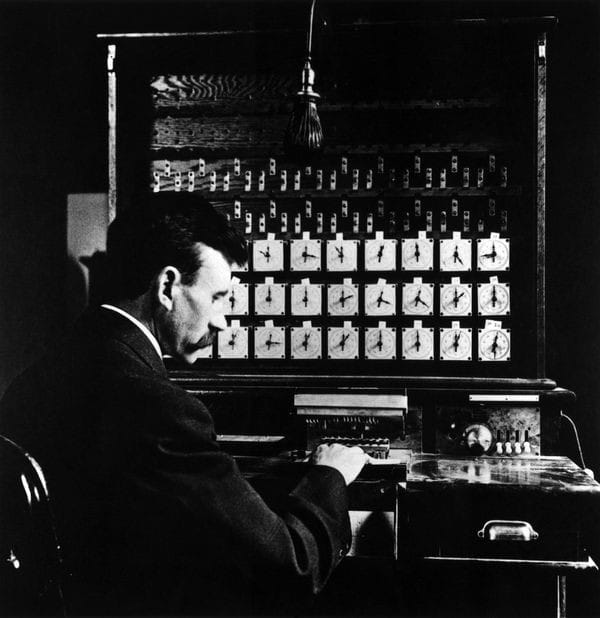

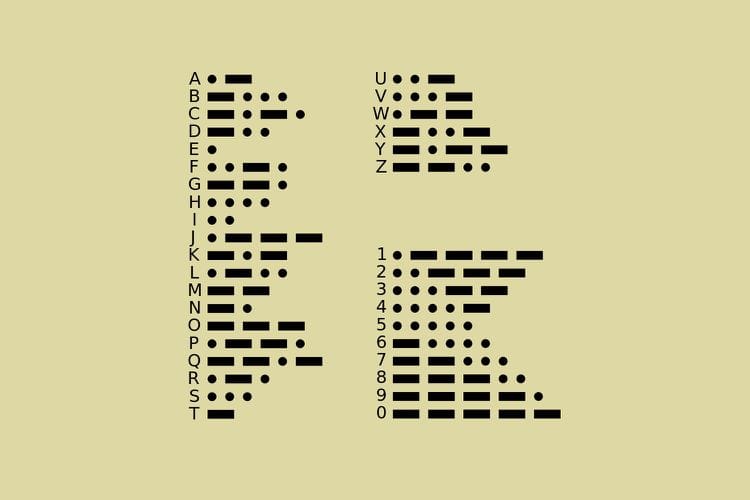

The system required two or more connected stations, a power source (typically a battery), and telegraph devices capable of sending and receiving coded signals. Skilled operators at each station translated messages into a series of electrical pulses, then back into readable text. These messages were usually sent using Morse code, a system of dots and dashes representing letters and numbers.

In the most common setup, pressing a key completed an electric circuit that produced audible clicks on the receiving end. Operators interpreted these clicks in real time, transcribing them by hand. The success of Morse's system depended not just on the technology, but on the human network of trained telegraphists who kept the signals flowing.

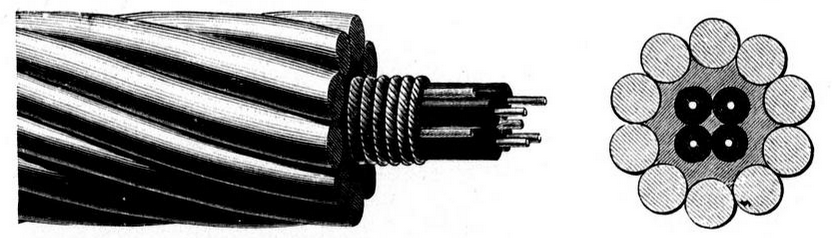

Samuel Morse, the inventor of the Morse Code (and renown painter), proclaimed his faith into the idea of submarine cables to carry telegraph communications in the 1840s. He did a test run with a cable isolated with hemp and rubber in the New-York harbor and successfully telegraphed through it, proving it could work. The discovery by western colonizers of gutta-percha trees and their magical, isolating latex occurred roughly at the same time. This material was successfully tested and finally chosen to make the first submarine cables.

The Submarine Telegraph Company managed to lay the first functional cable across the Channel, between France and England, in 1851.

By the mid-1850s, several successful submarine telegraph cables had been laid, linking Great Britain with Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Denmark. Ships like the William Hutt and Monarch played key roles in these early efforts, with the Monarch becoming the first vessel permanently equipped for cable-laying. In 1858, a cable connected the Channel Islands to the English coast, though it faced frequent breaks due to environmental damage—lessons that informed future cable-laying techniques.

The first transatlantic ambitions (1858)

The transatlantic telegraph cable was one of the 19th century’s boldest technological leaps—a project to connect Europe and North America with a direct line for instant communication. First completed in 1858 by the Atlantic Telegraph Company, it stretched from Valentia Island, Ireland, to Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. Messages that once took ten days by ship could now be sent in minutes. Queen Victoria even sent a 98-word message to U.S. President Buchanan—though it took 16 hours to transmit, prompting both celebration and head-scratching. Unfortunately, that first cable fizzled out after just three weeks, partly due to engineers using dangerously high voltages in a panic to boost weak signals.

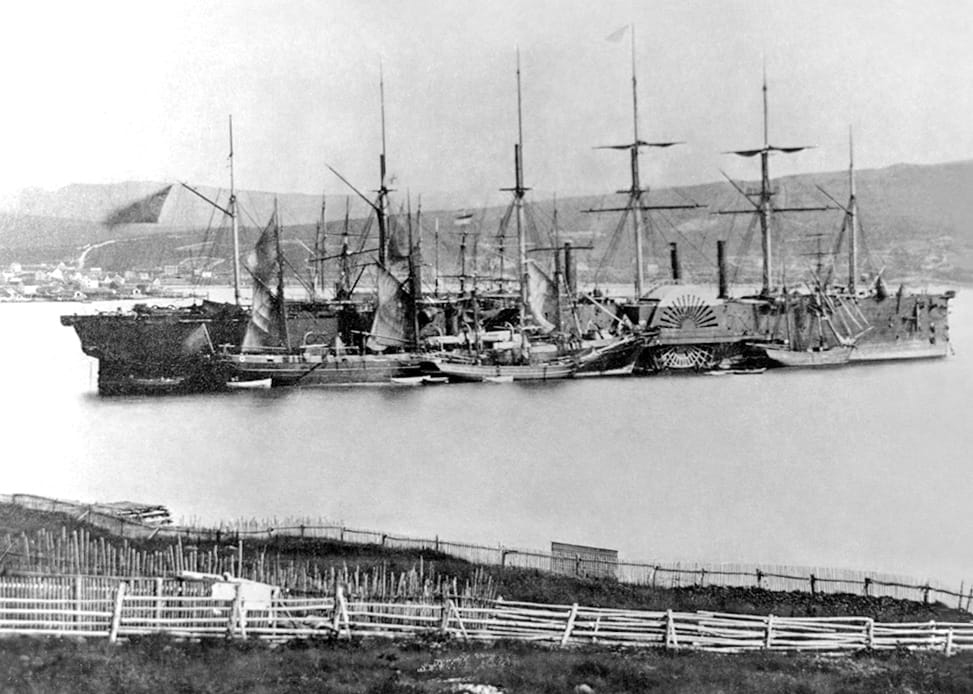

Undeterred, engineer Cyrus West Field and his team tried again—several times. In 1866, success finally came aboard the massive SS Great Eastern, the only ship large enough to carry the 4,200 kilometers of cable needed.

By the time the 1866 transatlantic cable was laid, the technology had taken a giant leap. It could transmit about eight words per minute—an enormous improvement over the sluggish 1858 cable, which managed barely one word every ten minutes. Behind this progress was a better understanding of signal behavior, thanks in part to later work by engineers like Oliver Heaviside and Mihajlo Pupin, who explained how signal distortion was caused by electrical imbalance in the cable—a problem that wouldn’t be truly solved until much later with the invention of load coils and repeaters.

Over the following decades, more cables were added—in 1873, 1874, 1880, and 1894—weaving an increasingly dense web between Europe and North America.

The full history of the first underwater transatlantic cable is told in this short documentary by the History channel:

Global expansion

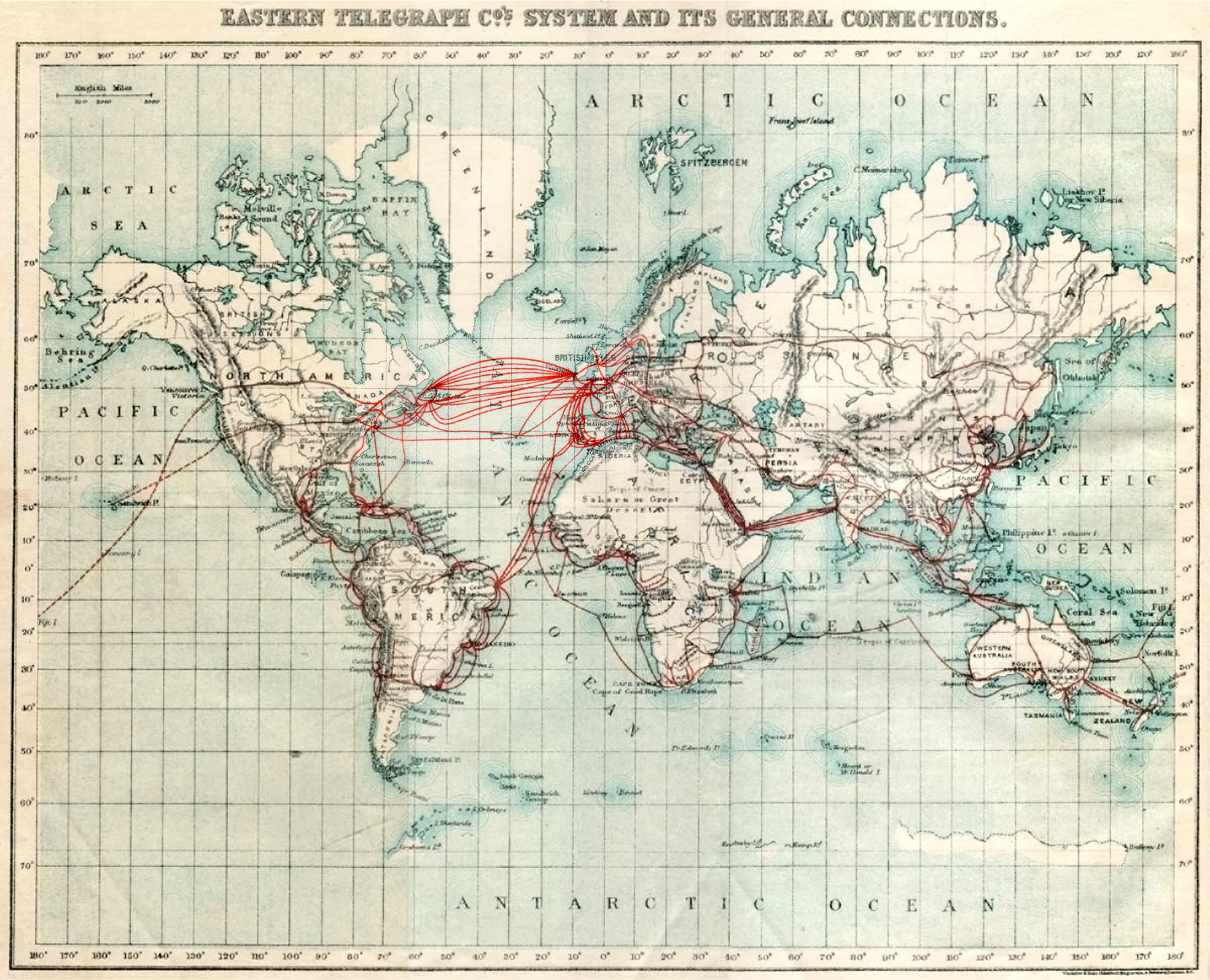

During the 1860s and 1870s, Britain (still - by far - the world leader on submarine cables) rapidly expanded its network eastward through the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean. A key milestone came in 1870, when Bombay was linked to London via a collaborative effort by four cable companies.

These companies merged in 1872 to form the Eastern Telegraph Company, a vast global operation led by John Pender. That same year, a sister company—known as the Extension—connected Australia to the network via Singapore and China. By 1876, the British Empire was fully linked by cable from London to New Zealand, completing a near-global communications chain.

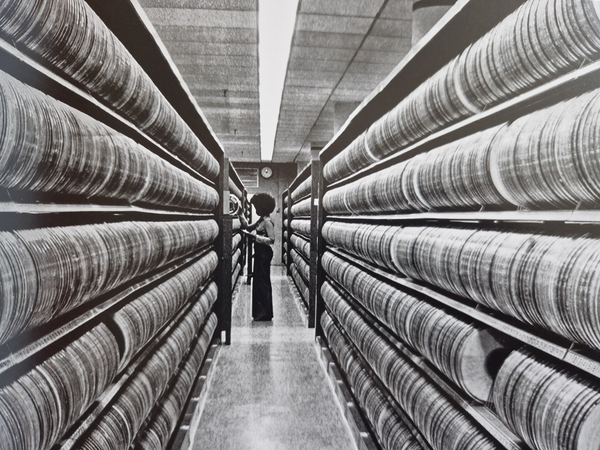

One station, Porthcurno in Cornwall, became a kind of nerve center for the British Empire’s communication system, with eleven cables fanning out across the globe.

It was nicknamed the "All Red Line" for the way British territories appeared on imperial maps—and in a way, it formed an early version of a global intranet. Still, none of these early cables had repeaters, meaning signal quality remained a limiting factor until the arrival of telephone cables like TAT-1 in 1956, which finally solved the problem with powered amplifiers.

Small cables, big impacts

The introduction of submarine telegraph cables had a transformative impact on global society, shrinking communication times from weeks to minutes. International diplomacy was among the first domains to change: during the Crimean War, Britain and France could coordinate military decisions in near real time—a dramatic shift from the delays of courier ships.

News agencies like Reuters built their reputation and reach on the speed offered by submarine telegraphy, transmitting market prices, political events, and even war updates faster than anyone else. This speed didn’t just inform the public—it reshaped public opinion, as reactions to international events became more immediate.

Economically, the cables enabled the first wave of globalized trade. Banks, shipping companies, and commodities traders could now operate with vastly reduced uncertainty. A cotton trader in Liverpool could learn of a harvest failure in Mississippi or a market fluctuation in Bombay the same day it happened. Stock exchanges in New York, London, and Paris became interlinked in ways that laid the groundwork for modern financial markets. The cables also reinforced colonial control, as imperial powers like Britain used rapid communication to manage their overseas territories more tightly, transmitting orders, intelligence, and administrative updates with unprecedented speed.

The making of cable hubs

The gradual deployment of submarine networks logically connected existing major urban centers (such as London, New-York, Porto, Bombay, Alexandria, Marseille, etc.), but also made some rather remote or little known places key hubs of the global telecommunication system. Those places are today often subject to heritage and conservation policies, some even have become UNESCO world heritage sites.

Valentia Island, Ireland – 1858

The European terminus of the first transatlantic telegraph cable in 1858, connecting to Newfoundland. Though that cable failed quickly, later cables from the 1860s established Ireland as a vital link between Europe and North America.

Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, Canada – 1866

Site of the successful landing of the 1866 transatlantic cable, enabling reliable communication between Europe and North America. The town became a strategic telegraph station for decades and is now a heritage site.

Source: The Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Website (source)

Porthcurno, United Kingdom – 1870

This small Cornish village housed the Eastern Telegraph Company’s station, connecting Britain to India and beyond via submarine cables. It became the British Empire's most important international communications hub and now hosts a museum on telegraphy.

Gibraltar – 1870s

A vital British outpost, Gibraltar was an intermediate relay for cables en route to Africa and the East. Its strategic geography continues to support modern submarine cable networks.

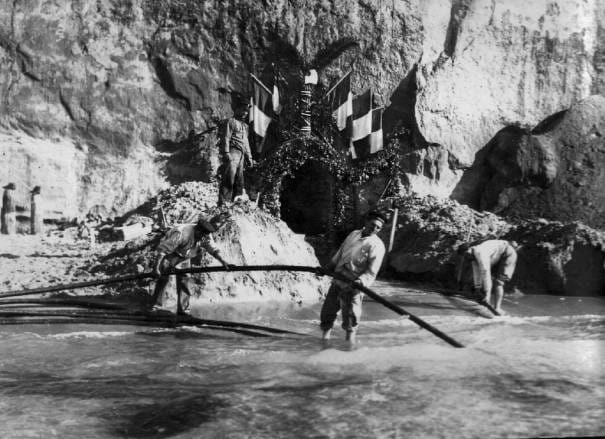

Anzio, Italy – 1870s

Anzio was a regional relay point for submarine cables connecting Italy to North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. Though overshadowed by Trieste and Naples, Anzio’s coastal position allowed Italy to project telegraphic influence across the sea, and later served crucial roles in WWII communications.

What came next

The shift from telegraph cables to telephone cables marked a turning point in global communication. While telegraphy dominated for over a century, by the mid-20th century, the world demanded voice transmission, not just coded text.

This need culminated in the launch of TAT-1 in 1956, the first transatlantic telephone cable, which used coaxial technology and underwater repeaters to carry multiple conversations simultaneously.

In the decades that followed, advances in electronics and materials led to digital transmission and, eventually, to fiber-optic cables in the 1980s and beyond—ushering in the high-speed, high-capacity networks that now underpin the Internet. You can find a detailed map of current submarine cable networks here.

We will come back to the history of the submarine cable network on Ones & Zeroes, as it is a major component of the digital infrastructure that deserves more attention than it usually gets.