Herman Hollerith, the Census Machines and the birth of IBM

It all started with a very ambitious and painfully slow project: the United States National Census.

The rise of the Tabulation Project

In the late 1880s, the United States confronted a pressing administrative challenge: the decennial census of 1880 had taken between six and eight years to process, rendering its demographic insights obsolete by the time they became available. This delay threatened democratic accountability, fiscal planning, and public trust.

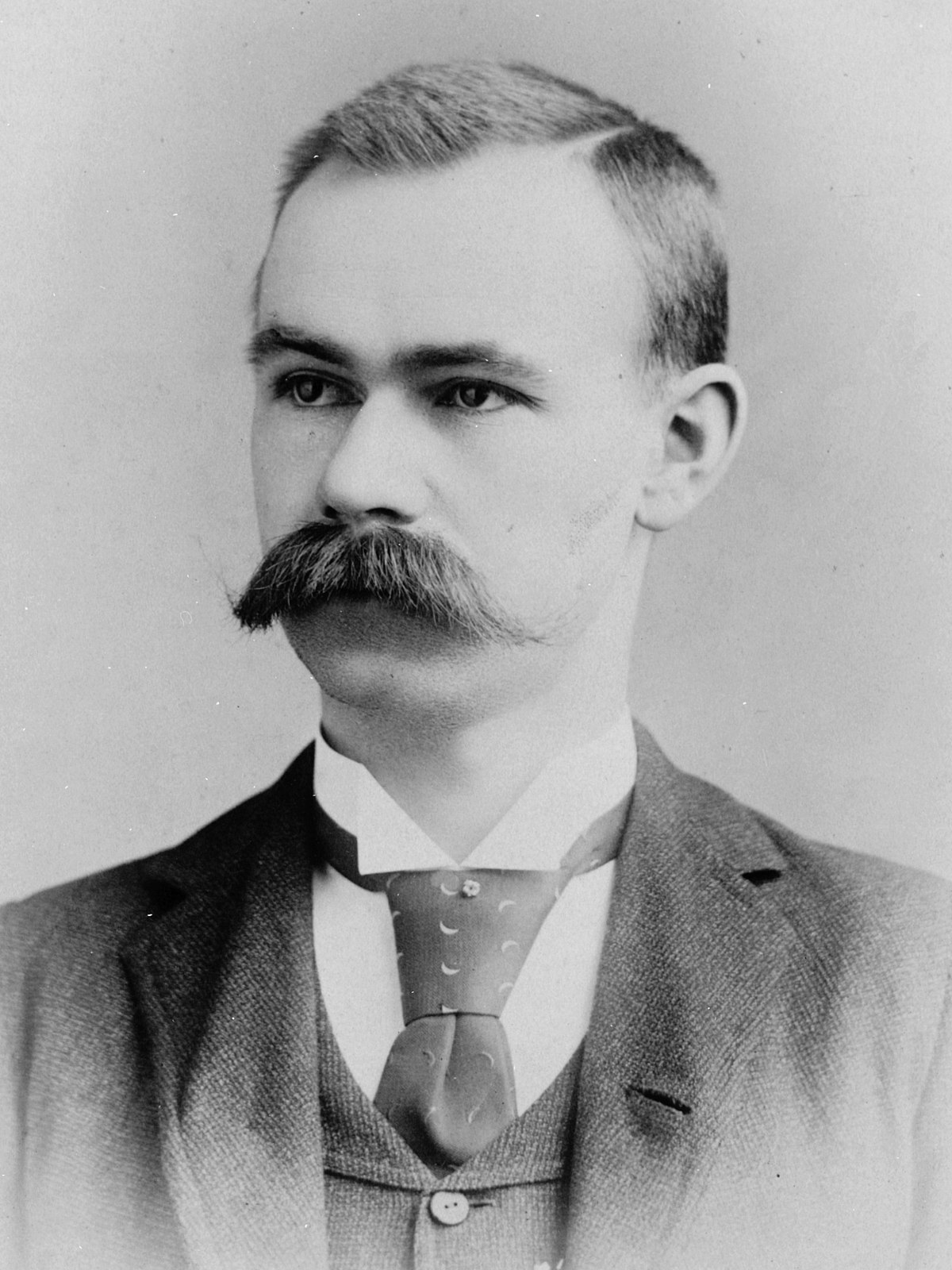

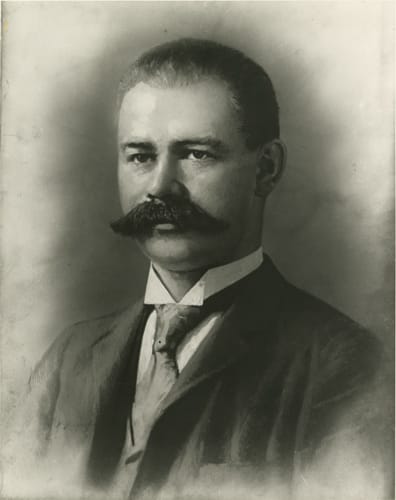

Herman Hollerith, - an american engineer of German descent - with a degree from Columbia University’s School of Mines (1879), began working at the U.S. Census Bureau as a statistician shortly after graduation. It was during his time there, particularly in the years following the 1880 census, that he became acutely aware of the immense challenge of processing growing volumes of population data. The tabulation process was still entirely manual and excruciatingly slow, often taking nearly a decade to complete a single census cycle. This direct experience with administrative overload and inefficiency inspired Hollerith to focus his doctoral research on developing a mechanical solution for data tabulation — a decision that would lay the groundwork for one of the most consequential inventions in the history of data processing.

After receiving his Engineer of Mines (EM) degree at age 19, Hollerith worked on the 1880 US census, a laborious and error-prone operation that cried out for mechanization. After some initial trials with paper tape, he settled on punched cards (pioneered in the Jacquard loom) to record information, and designed special equipment – a tabulator and sorter – to tally the results. His designs won the competition for the 1890 US census, chosen for their ability to count combined facts. These machines reduced a ten-year job to three months (some sources give different numbers, ranging from six weeks to three years), saved the 1890 taxpayers five million dollars, and earned him an 1890 Columbia PhD.

This was the first wholly successful information processing system to replace pen and paper. Hollerith's machines were also used for censuses in Russia, Austria, Canada, France, Norway, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines, and again in the US census of 1900. - Columbia History Of Computing

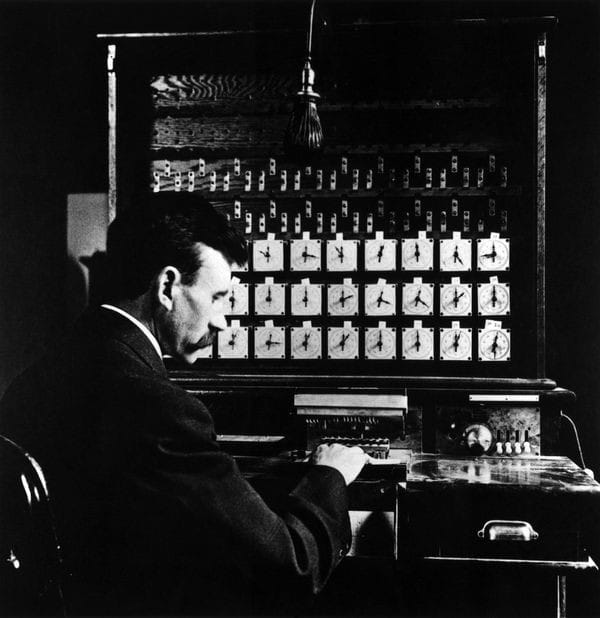

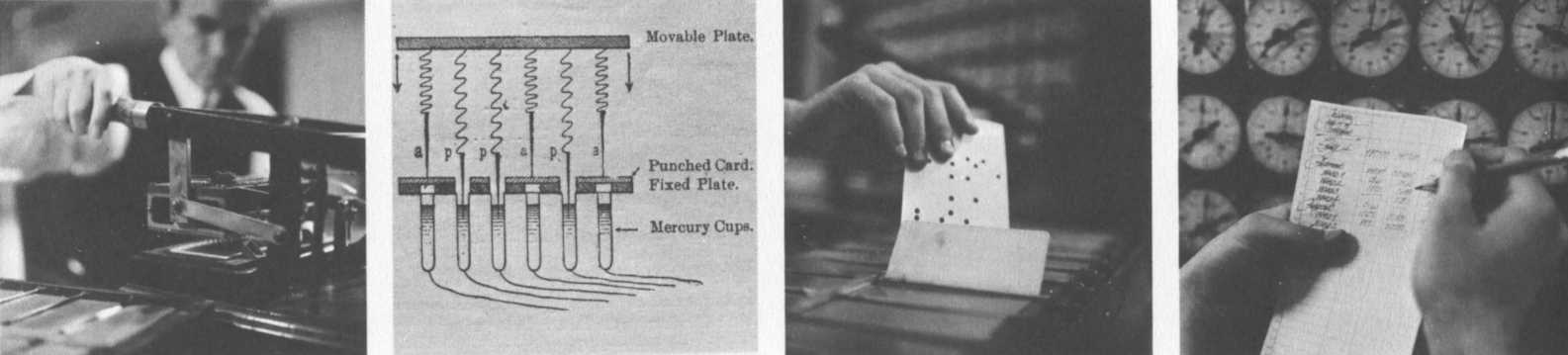

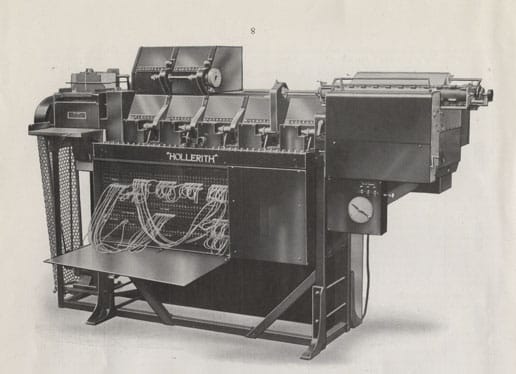

Hollerith's genius lay in combining simplicity with mechanical robustness. The core of his system involved paper-based punch cards—each card representing an individual respondent—with positions designated for various attributes. To automate tabulation, he devised a mechanism in which stacks of cards were placed into racks that were lowered onto mercury-coated contacts. Whenever a hole aligned with a contact, an electric circuit closed, triggering a mechanical counter. Cards could also be routed into sorted compartments based on their encoded data.

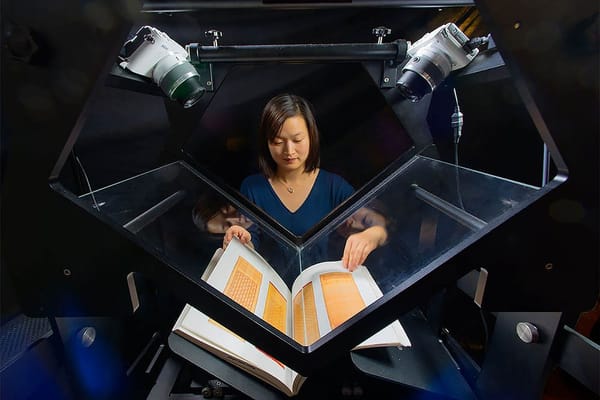

Keypunch machines automated the encoding process, enabling clerks to punch hundreds of holes per hour. Verification stations ensured accuracy by re-checking each card. Card sorters, using mechanical switches, grouped cards by fields such as ZIP code or occupation. Finally, tabulators aggregated results into printed totals or reports. This assembly-line of machines and clerks created an early cyber-physical system—efficient, scalable, and remarkably reliable for its era.

Hollerith’s innovation was not the labor of a solitary inventor. While at Columbia, he was mentored by prominent figures such as John Runkle and William D. Whitney, who fostered an interdisciplinary mindset bridging applied science, engineering, and governance. These scholarly connections expanded his conceptual toolkit and provided early institutional validation.

Runkle was a prominent figure in late 19th-century American engineering education. After serving as president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he returned to Columbia University—first at its School of Mines and later the nascent Teachers College. An advocate for practical science, Runkle encouraged students like Hollerith to apply engineering solutions to real-world problems. His emphasis on empirical experimentation and mechanical invention set the stage for Hollerith’s insistence on combining rigorous academic work with industrial implementation.

Post-graduation, Hollerith's employment at the Census Bureau and his membership within the American Social Science Association and the American Institute of Electrical Engineers gave him both practical insights and legitimacy. Moreover, his role in professional networks opened doors to bureaucratic audiences seeking innovative solutions. These intellectual and institutional alliances were instrumental in securing both acceptance and funding for his tabulation project.

From tabulation machines to data factories

By the mid-1890s, Hollerith’s tabulating machines had transcended their American origins. The Tabulating Machine Company (founded in 1896) pursued international licensing with precision. In Britain, the British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM) was established to service the Colonial Office and burgeoning industrial clients. In Germany, Dehomag (Deutsche Hollerith-Maschinen Gesellschaft) became emblematic of how efficient data-processing could bolster state bureaucracy. France opened its market to Hollerith systems for railway statistics, insurance actuarial, and municipal sewer planning, and gave birth to the Bull company. Russia, Austria-Hungary, Scandinavia, and even parts of Latin America soon followed suit.

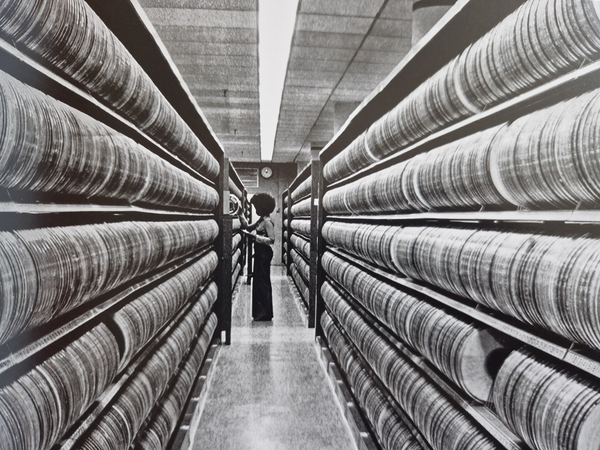

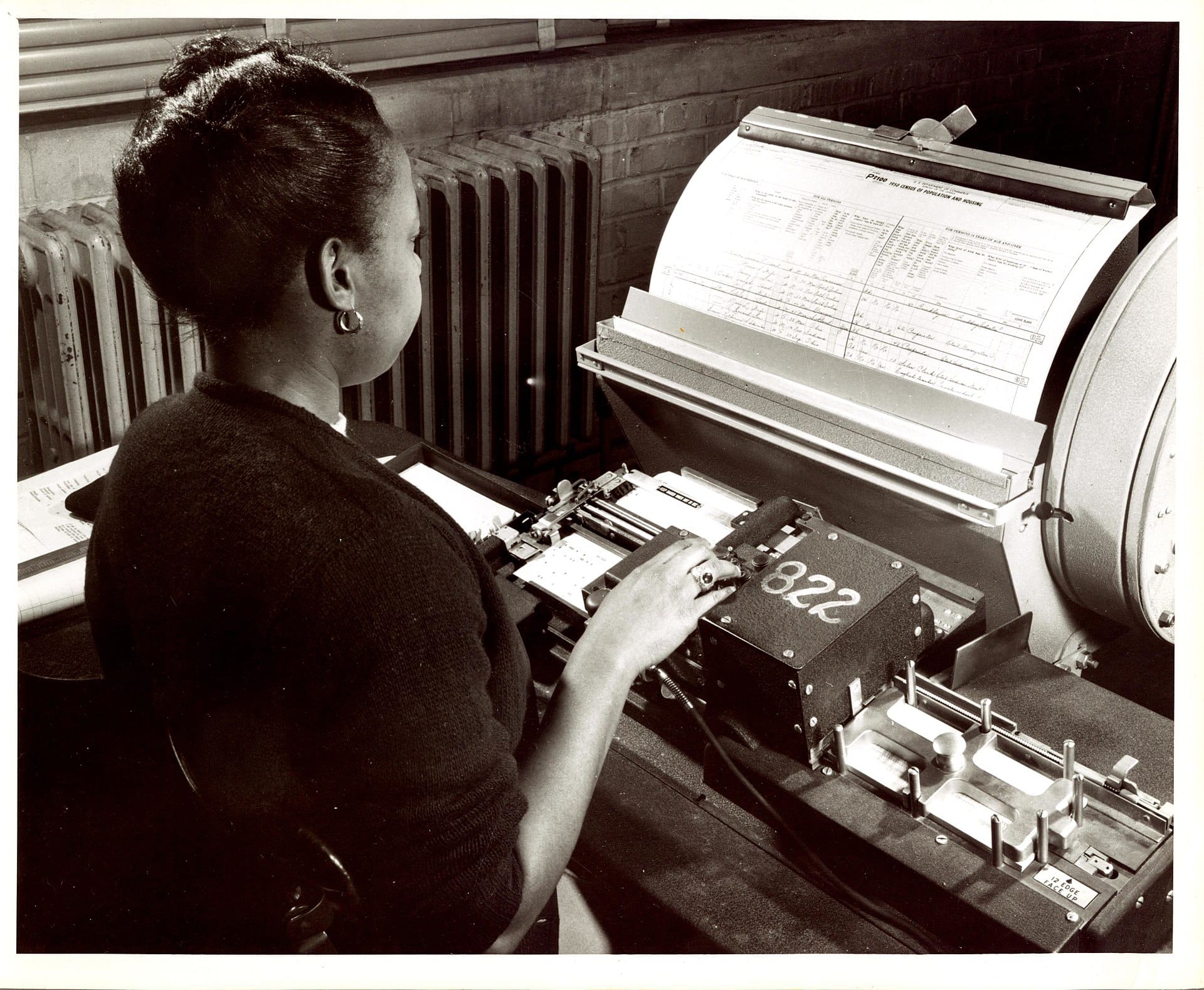

These punch-card machines catalyzed the rise of “data factories”. Keypunch operators, predominantly women, meticulously encoded data onto cards. A parallel verification process ensured accuracy; increasingly, cards fed through sorting devices organized information by region, product, or demographic segment; finally, tabulators mechanically aggregated results. These workshops were both clerical and mechanical in nature, blurring the lines between factory and office. The result was not simply automation, but the creation of a new labor economy: a skilled, mostly female workforce operating machinery and managing critical infrastructure. These units became vital to government census-taking, epidemic mapping, railway scheduling, and industrial analytics—many years before the advent of electronic computers.

The Computing-Tabulating Machine Company & IBM

Industrial and governmental demand for these systems created fertile ground for corporate consolidation. In 1911, financier Charles Flint orchestrated a pivotal merger: Hollerith’s Tabulating Machine Company combined with firms specializing in time-recording apparatus, commercial scales, and meat slicers, birthing the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR). By pooling technologies and administrative reach, CTR expanded its international footprint and standardized operations across domains. With over 1,300 employees and active installations throughout Europe and North America, CTR represented the meeting point of industrial-scale manufacturing and large-scale data processing.

In 1924, under the leadership of Thomas J. Watson Sr., CTR rebranded as International Business Machines (IBM)—a name that would become synonymous with corporate computing infrastructure.

Rather than selling machines outright, IBM developed enduring relationships with governments and businesses via hardware leases and routine maintenance contracts. This model established IBM not merely as an equipment supplier, but as a trusted systems partner—in offices, rail yards, census bureaus, and research laboratories worldwide. Hollerith, meanwhile, transitioned to a consultative role until 1921, gradually giving way to industrial executives as the field professionalized.

Patents & Rights

Hollerith’s foundational patents—granted in 1889—covered the tabulating machine, card reading apparatus, and punched-card feeding mechanisms. These intellectual property rights granted him a commanding edge in the nascent industry, allowing him to license technology while simultaneously encouraging rivals to innovate.

In the United States, the Powers Accounting Machine Company developed its own tabulating solutions, prompting a wave of litigation and patent cross-licensing. In France, Bull Electronics engineered similar machines, later becoming a distinct force in European computing. In Britain and Germany, BTM and Dehomag respectively grew into dominant national players.

The competitive tensions extended beyond legal jousting. Each company advanced mechanical refinements: automatic card feeders, enhanced sorting algorithms, and faster tabulation speeds.

CTR—soon IBM—embarked on a strategy of buying out or merging with its rivals. Despite attempts at regulatory challenge (notably the U.S. government’s 1936 antitrust intervention into IBM's punch-card leasing practices), IBM maintained dominance until the era of digital computers dawned in the 1950s and 1960s. These early intellectual battles shaped the trajectories of modern computing industries, demonstrating how disputes over card-slot mechanisms and solenoid timing could influence global data infrastructure for decades to come.

Hollerith's Legacy

Herman Hollerith retired in the early 1920s, after seeing his inventions reshape not just the U.S. Census but data processing across industries and continents. He remained on the board of the company that became IBM for several years, though the firm’s future direction—under Thomas J. Watson’s leadership—moved well beyond his original machines.

Hollerith died in 1929 at the age of 69, just as the Great Depression began and as the world he helped mechanize turned toward electronic computing. Though overshadowed in popular memory by later tech pioneers, Hollerith's punch card system laid the foundation for modern data infrastructures. His name may not be widely known today, but the logic of tabulation, categorization, and large-scale data control he developed remains embedded in the architecture of our digital lives.

Hollerith is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Hollerith cards were named after Herman Hollerith, as were Hollerith constants, used in the FORTRAN coding programs to allow manipulation of character data.

Operating the machines: a demonstration, and a testimony

An interview with Bubbles Whiting who, in her early career, used punch cards in her everyday work life. From the Centre for Computing History.

Sources

https://www.columbia.edu/cu/computinghistory/hollerith.html