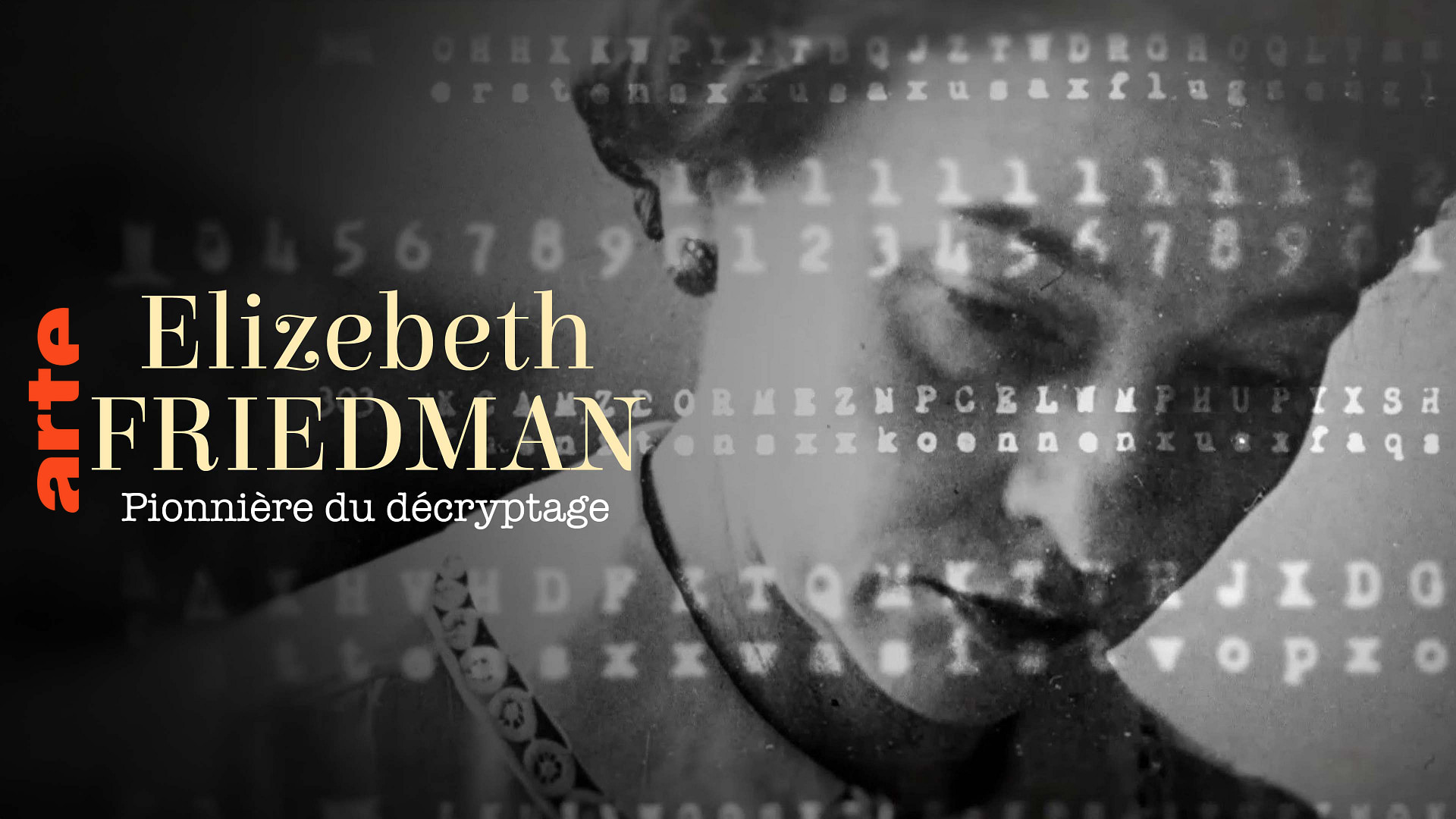

Elizebeth Smith Friedman, the Cryptoanalyst who won Wars and defeated the Mob

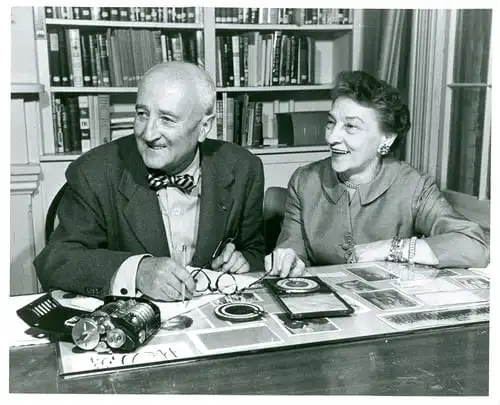

Known to posterity as "The Mother of Cryptology," Elizebeth Friedman's extraordinary career spanned three decades and fundamentally shaped the foundations of modern intelligence work.

From breaking enemy codes in two world wars to dismantling criminal networks during Prohibition, Friedman's intellectual brilliance and dedication helped secure American interests through some of the nation's most turbulent periods.

From a Quaker family to English literature

Born on August 26, 1892, into a large Quaker family in the small town of Huntington, Indiana, Elizebeth Smith was the youngest of ten children. Her father John Smith and mother Sopha Strock Smith raised their daughter with the Quaker values of integrity, equality, and quiet determination—principles that would later guide her through a career where recognition was often denied due to the classified nature of her work and the gender barriers of her era. From an early age, Elizebeth harbored dreams that extended far beyond the confines of rural Indiana, envisioning a life of intellectual adventure and meaningful contribution.

Her passion for literature, particularly poetry, led her to pursue higher education at Hillsdale College in Michigan, where she immersed herself in the study of English, German, Latin, and Greek. Graduating in 1915 with a degree in English literature, she initially followed one of the few professional paths available to educated women of her generation: teaching. However, the constraints of the classroom quickly proved stifling for her restless intellect. The teaching position was short-lived, and by spring 1916, she had returned to live with her parents, uncertain of her future but determined to find work that would challenge her mind and satisfy her yearning for purpose.

The Great War and the Birth of American Cryptanalysis (1916-1918)

Elizebeth Smith's entry into the world of cryptology began with literary curiosity. In 1916, while visiting the Newberry Library in Chicago in search of meaningful employment, a chance conversation with a librarian would change the course of her life forever. The librarian mentioned an unusual position at Riverbank Laboratories in nearby Geneva, Illinois, where an eccentric millionaire named George Fabyan was funding research into one of literature's most enduring mysteries: whether Sir Francis Bacon had written the works attributed to William Shakespeare.

Riverbank Laboratories represented one of the first facilities in the United States dedicated to the study of cryptography. Under the guidance of Elizabeth Wells Gallup, who ran the campus cipher school and had published groundbreaking work on Francis Bacon's bilateral cipher in 1899, Elizebeth began her education in the arcane art of finding hidden messages within seemingly innocent text. The work involved painstakingly examining Shakespeare's folios and quartos, searching for minute variations in typefaces that might encode secret messages proving Bacon's authorship of the plays.

Though the Shakespeare-Bacon investigation would ultimately prove fruitless—Elizebeth and her colleague William Friedman, whom she met and later married at Riverbank, found no convincing evidence of hidden codes—the training proved invaluable. Under Gallup's tutelage, Elizebeth developed the fundamental skills of pattern recognition, methodical analysis, and logical deduction that would serve as the bedrock of her future career. More importantly, she discovered an innate talent for seeing patterns that others missed, a gift that would soon prove critical to American national security.

Colonel George Fabyan, recognizing the strategic importance of his cryptographic facility, offered Riverbank's services to the War Department. Suddenly, Elizebeth Smith found herself on the front lines of America's intelligence war.

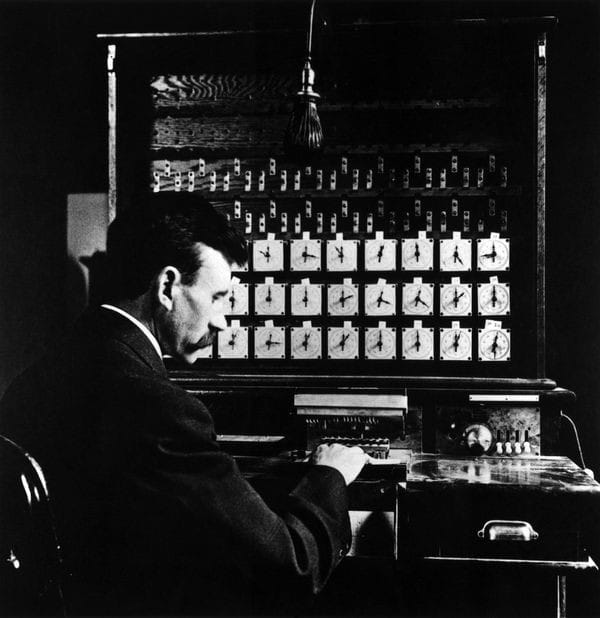

Working alongside William Friedman and a small team of dedicated cryptanalysts, Elizebeth tackled an enormous variety of enemy communications. German diplomatic and military messages, intercepted wireless transmissions, and suspected spy communications all passed through her hands. The work was intensive and often frustrating—cryptanalysts of the era worked entirely with pencil and paper, relying solely on their intellectual capabilities to unravel complex encoding systems. There were no mechanical aids, no electronic computers, just the human mind against the ingenuity of enemy code makers.

The young cryptanalyst also played a crucial role in breaking codes used by German wireless stations throughout Latin America. These stations served as communication hubs for German intelligence operations in the Western Hemisphere, coordinating everything from submarine operations to sabotage activities. By successfully decrypting these communications, Elizebeth provided American and Allied forces with invaluable intelligence about German plans and capabilities.

By the war's end in 1918, Elizebeth Smith Friedman had established herself as one of America's foremost cryptanalysts. Her work had helped transform cryptography from an amateur pursuit into a rigorous scientific discipline, laying the groundwork for the professional intelligence services that would emerge in the following decades.

Prohibition and the War Against Organized Crime (1920-1933)

The passage of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1920 and the subsequent enforcement of Prohibition created an entirely new category of criminal enterprise in America. Bootleggers, rumrunners, and organized crime syndicates quickly recognized that radio communications offered both unprecedented coordination capabilities and new vulnerabilities. Criminal organizations began employing sophisticated codes and ciphers to coordinate their operations, believing their communications were secure from law enforcement. They had not reckoned with Elizebeth Smith Friedman.

In 1925, recognizing the critical need for cryptanalytic support in combating smuggling operations, the U.S. Coast Guard recruited Elizebeth to serve as their chief cryptanalyst.

Working from a small office with just one clerk, Elizebeth faced an enormous challenge. The 12,000-mile American coastline provided countless opportunities for smugglers, and their radio networks had grown increasingly sophisticated. Criminal organizations employed code systems ranging from simple substitution ciphers to complex book codes based on popular novels. Some groups changed their codes weekly, while others employed multiple overlapping systems to confuse potential eavesdroppers.

Elizebeth's approach combined systematic methodology with innovative techniques adapted to the unique challenges of criminal cryptography. Unlike military codes, which often followed established protocols and conventions, criminal codes reflected the practical needs and limited education of their users. This paradoxically made them both easier and harder to break—easier because they often contained logical inconsistencies and shortcuts, harder because they didn't follow the predictable patterns that military cryptanalysts had learned to exploit.

Her most famous success came in dismantling the communication networks of major rum-running syndicates operating in the Gulf of Mexico and along the Atlantic seaboard. These organizations had developed remarkably sophisticated operations, with mother ships stationed in international waters coordinating with networks of smaller vessels that would ferry alcohol to shore. Their coded communications covered everything from weather conditions and Coast Guard movements to financial arrangements and delivery schedules.

The intelligence provided by Elizebeth's codebreaking operations proved devastating to criminal organizations. Coast Guard vessels, armed with advance knowledge of smuggling operations, could position themselves to intercept criminal vessels with remarkable precision. The psychological impact was equally significant, as criminal organizations realized that their supposedly secure communications were being read by law enforcement. Some groups abandoned radio communications entirely, reverting to less efficient but more secure methods that significantly hampered their operations.

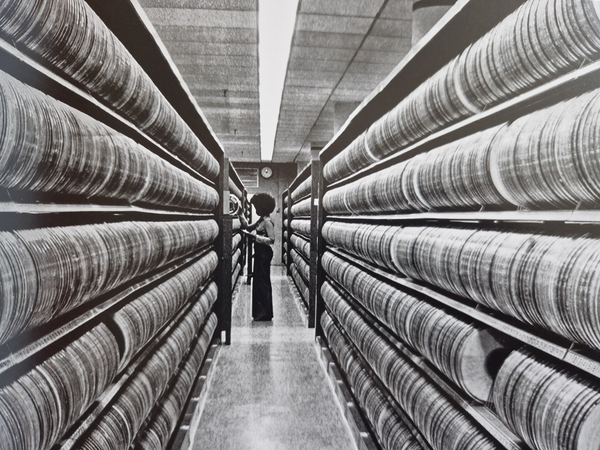

Over the course of her Coast Guard service, Elizebeth and her small team cracked approximately 12,000 encrypted messages. This intelligence directly resulted in 650 criminal prosecutions and the seizure of vessels, equipment, and contraband worth millions of dollars. More importantly, her work helped establish the principle that sophisticated cryptanalytic support was essential to modern law enforcement operations.

Elizebeth's expertise was not confined to the technical aspects of codebreaking. She frequently served as an expert witness in federal court cases, explaining complex cryptographic evidence to judges and juries who had never encountered such material.

The end of Prohibition in 1933 marked the conclusion of one of the most successful intelligence operations in American law enforcement history. Elizebeth Smith Friedman had single-handedly created the Coast Guard's cryptanalytic capability and used it to deliver crushing blows to organized crime networks. Yet even as one chapter of her career closed, international events were already brewing that would soon call upon her expertise once more.

World War II and the Final Victory (1939-1945)

As Europe plunged into war in 1939 and the United States moved inexorably toward involvement in the global conflict, Elizebeth Smith Friedman found herself once again at the center of American intelligence operations. The world of cryptography had evolved dramatically since the Great War, with new technologies and mathematical approaches revolutionizing the field. Yet the fundamental skills that had made Elizebeth one of America's premier cryptanalysts—pattern recognition, logical analysis, and methodical perseverance—remained as relevant as ever.

Unlike her World War I service, which had been conducted in relative obscurity at a private research facility, Elizebeth's World War II contributions came as an official member of the U.S. Navy's cryptologic organization. The Navy had recognized the critical importance of signals intelligence in modern warfare and had assembled teams of the nation's finest cryptanalysts to tackle the enormous challenge of enemy communications. Despite the institutional skepticism about women's capabilities that still pervaded military organizations, Elizebeth's reputation and proven track record earned her a position of significant responsibility.

Her primary focus during this period was on German and Japanese diplomatic and intelligence communications throughout Latin America. The Axis powers had established extensive networks of agents, sympathizers, and communication facilities across Central and South America, viewing the region as both a potential source of strategic materials and a back door for operations against the United States. These networks employed sophisticated cryptographic systems that had evolved far beyond the relatively simple codes of the previous war.

One of Elizebeth's most crucial contributions involved unraveling German spy networks operating throughout South America. German intelligence services had recruited local agents and established radio stations that provided a steady stream of intelligence about Allied shipping, troop movements, and industrial activities. These communications were encrypted using variants of the German diplomatic cipher system, which employed complex mathematical algorithms and frequent key changes designed to defeat cryptanalytic attacks.

The technical challenges were formidable. German cryptographers had learned from their World War I experiences and had developed systems that incorporated multiple layers of encryption, irregular key patterns, and sophisticated mathematical transformations. Moreover, the German operatives in South America often modified standard procedures to adapt to local conditions, creating variants that didn't appear in captured codebooks or previously broken systems.

Elizebeth's approach combined traditional cryptanalytic methods with new mathematical techniques that were transforming the field. She developed systematic approaches for identifying the underlying structure of modified German systems, often working with incomplete or corrupted message fragments intercepted by Allied listening stations scattered across the hemisphere. Her work required not only cryptographic expertise but also deep knowledge of German intelligence procedures, South American geography and politics, and the practical constraints faced by clandestine radio operators.

The scope of Elizebeth's World War II contributions extended beyond individual cryptanalytic successes to broader organizational and methodological innovations. She helped develop new training programs for cryptanalysts, created systematic approaches for handling high-volume message traffic, and established quality control procedures that ensured the accuracy of critical intelligence. Her work contributed to the professionalization of American signals intelligence and helped establish standards and practices that would endure long after the war's end.

Unlike her earlier career phases, where her contributions were often minimized or attributed to others, World War II brought a degree of official recognition for Elizebeth's expertise.

She received commendations from Navy leadership and was acknowledged as one of the service's most valuable cryptanalysts. Yet even this recognition came with limitations—the classified nature of her work meant that her achievements remained largely unknown to the public, and gender-based discrimination continued to limit her advancement opportunities within the military hierarchy.

The war's end in 1945 marked the conclusion of an extraordinary career that had spanned three decades and fundamentally shaped American intelligence capabilities. From her humble beginnings searching for hidden messages in Shakespeare's plays to her sophisticated analysis of Axis communications networks, Elizebeth Smith Friedman had helped transform cryptanalysis from an amateur pursuit into a rigorous scientific discipline. Her innovations in methodology, training, and organization had created institutional capabilities that would serve American interests throughout the Cold War and beyond.

When Elizebeth Smith Friedman finally retired from government service, she left behind a transformed American intelligence community.

The methods she had developed, the standards she had established, and the precedents she had set would continue to influence cryptanalytic practice for decades to come. In the shadows where intelligence professionals do their work, protecting secrets and serving their nation without expectation of public recognition, her example would continue to inspire those who understood that true service requires not acclaim, but excellence.

Additional resources