Douglas Engelbart, the Mother of All Demos & where the Mouse comes from (1968)

Douglas Engelbart was an American engineer and computer science pioneer known for leading - with his team from the Standford Research Institute - "the Mother of all Demos" in 1968. His contributions to computer sciences, and especially to the field of human-computer interactions, go way beyond the iconic demo often associated with his name.

Douglas Engelbart is described by its peers as a visionary man, who gave himself a life mission and stuck with it, making him both widely recognized for being ahead of his time, but also left him sort of misunderstood. His ambitions were collective and collaborative as much as technological, and he wanted to pursue this vision further instead of stopping on the way to start producing commercial personal computers.

Engelbart's work indeed widely inspired Steve Jobs and many others for the creation of the first personal computers, though they mostly copied the mouse and graphic interface while leaving aside the most important components for Engelbart: the network and collaborative capacities, and the idea of a "collective IQ" going beyond individual work.

Probably a bit blessed and a bit cursed too, Engelbart envisioned almost thirty years in advance what personal computers plugged in networks could do, from videoconference (hello Zoom) to collaborative document editing (hello Google Docs), hypertext (hello... the Web), functionalities such as the copy-paste, selecting and moving a piece of text on a list (which he demonstrated with a grocery shopping list). Oh, and he also invented the mouse on the way, which he didn't even considered as a major innovation in itself. What mattered was the system he was creating and the vision he was carrying to make humanity more intelligent as a whole (and not just individuals more productive).

Engelbart before Standford

Engelbart worked as a radar technician in the Navy during two years, and then as a wind tunnel technician for NASA Ames before obtaining his electrical engineering MS (Master of Science) and PhD degrees at the University of California, Berkeley.

Those experiences combined led Engelbart to gain clarity on several key concepts:

- The first one was "scaling", especially in relation to the Moore law that was starting to emerge in the microprocessor community. Gordon Moore, cofounder of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, noted in 1965 that "the number of components per integrated circuit had been doubling every year and projected this rate of growth would continue for at least another decade". This not only meant that computing power was going to increase rapidly, but that it would become cheaper and therefore accessible to the public at a wider scale in the years to come. Computers were becoming the way to achieve anything significant.

- The second concept was the idea of interacting through visual graphic interfaces (inspired by his radar experience in the Navy) to not only visualize information, but to manipulate it on a screen. This was the early premises of the WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) interfaces. In an era dominated by command line terminals and printed paper, envisioning such a "user-friendly" way to interact with computers was an absolute revolution (some claim Engelbart invented "user-friendliness" itself). Engelbart was also inspired by music and music sheets, thinking of the user as the orchestra conductor who should be able to edit and navigate through a universe of knowledge, all through the machine using a keyboard and... a mouse.

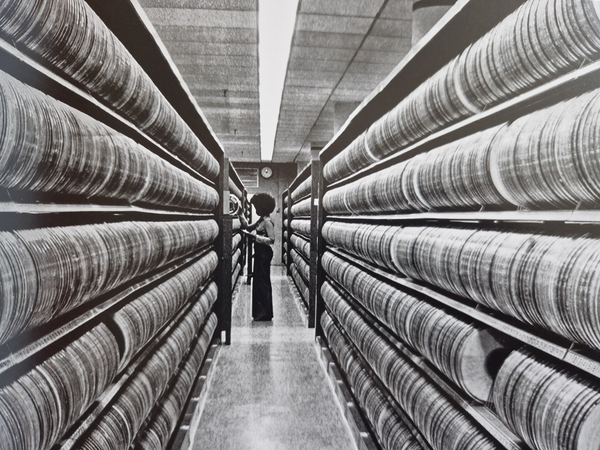

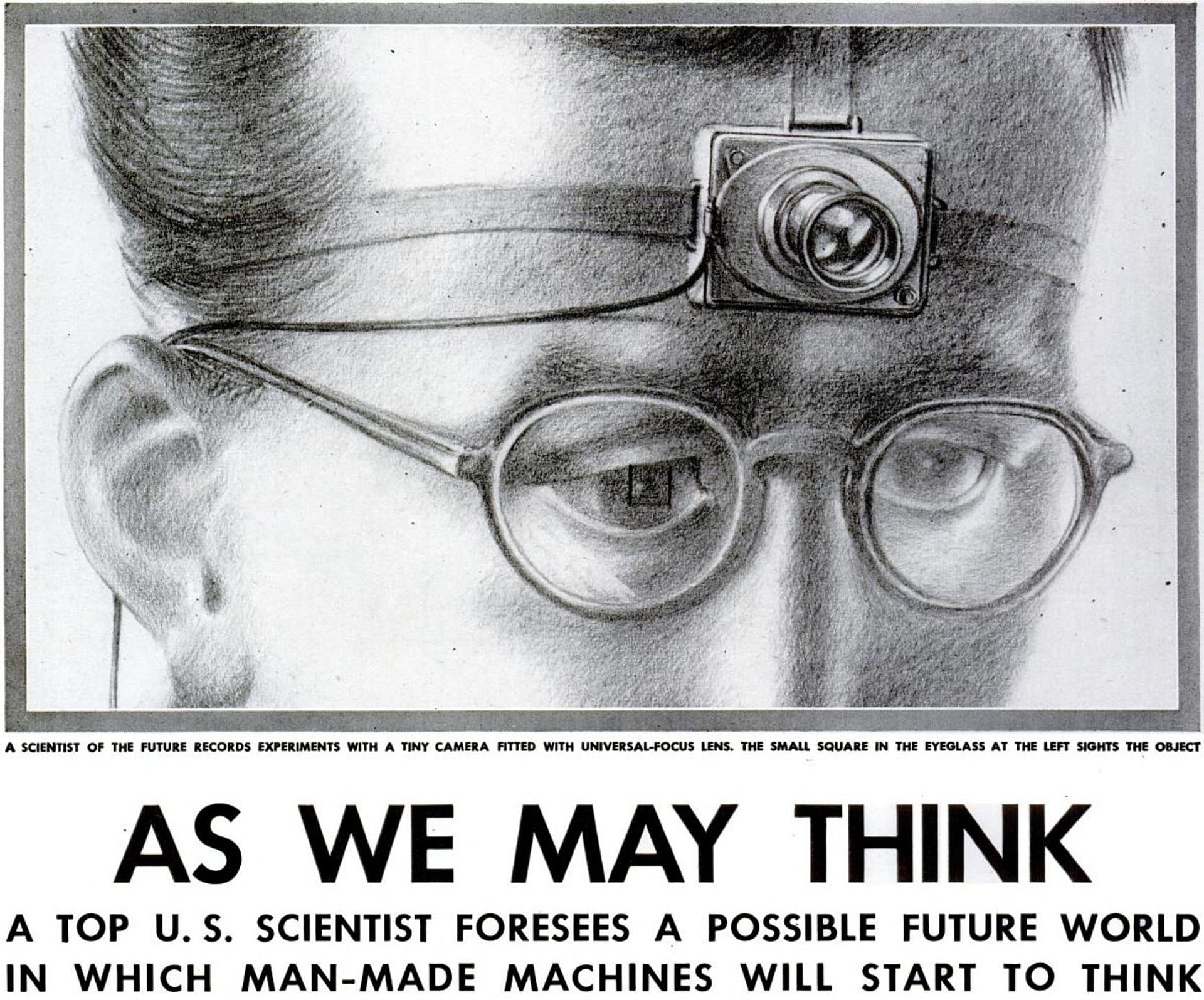

- The third concept is more of a general vision, coming from the article "As We May Think", written in 1945 by engineer and researcher Vannevar Bush. Written in the context of the war and nuclear bombings, Bush's essay argues that humanity should focus on collective memory, information preservation and find new ways to share knowledge. He crafted the idea of a Memex that would compress all the books and make "all the knowledge" accessible by anyone. In essence, the Memex "reflects a library of collective knowledge stored in a piece of machinery". At the time, Bush envisioned this on microfilms coupled with screen viewers and cameras. The full article by Bush can be found here (source: MIT).

The difficulty seems to be, not so much that we publish unduly in view of the extent and variety of present-day interests, but rather that publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record. The summation of human experience us being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships. - Vannevar Bush (1945)

Bush stated in 1945 that the amount of information produced by human societies was expanding faster than the available technologies to manage it were progressing, leading to a wide gap in our ability to process and use that knowledge at scale.

This inspired Engelbart to make it his life mission to increase human's intelligence through a collective and collaborative effort, relying on computers to achieve that vision for "a better world".

The Augmentation Research Center at Stanford Research Institute

Englebart took a position at the SRI (Stanford Research Institute) in 1957, in Menlo Park, California. A few years later, after contributing to several patents, Englebart formalized for the first time what would be his long term vision in a report titled "Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework" (available here), published in 1962. This report got Englebart funding from ARPA, and he was able to recruit a research team for his new Augmentation Research Center.

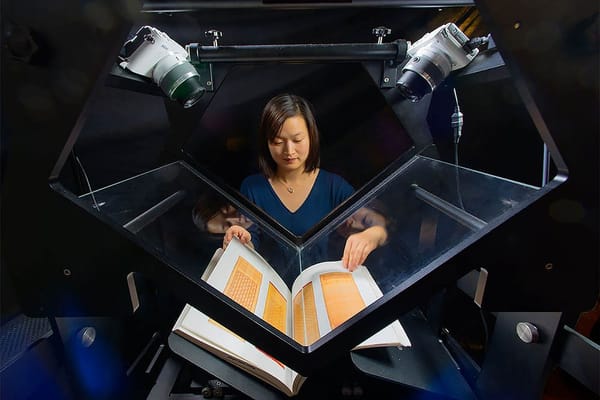

The Augmentation Research Center (ARC) became the central force behind the creation of the oN-Line System (NLS). The team developed a wide range of groundbreaking interface technologies, including bitmapped screens, the mouse, hypertext, collaborative editing tools, and the early foundations of what would later become the graphical user interface.

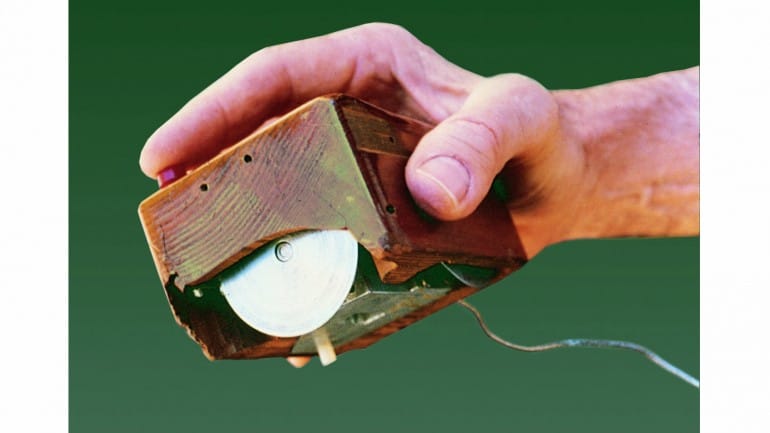

One of the most iconic inventions from this period was of course the computer mouse, co-developed with Bill English, his lead engineer, sometime before 1965. Engelbart applied for a patent in 1967 and received it in 1970. The device — described in the patent as an "X-Y position indicator for a display system" — consisted of a wooden shell with two metal wheels. It later became known as the "mouse" because of the cable protruding like a tail.

The cursor itself — initially an upward-pointing arrow — was eventually slanted left when adopted at Xerox PARC, to help distinguish it from text in low-resolution environments. That angled arrow, with its 45-degree slant, has since become a universal visual symbol of computer interaction.

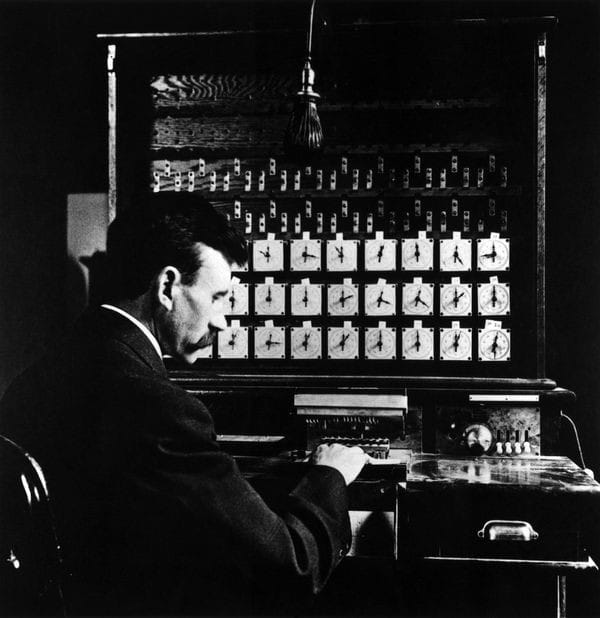

Engelbart demonstrated the mouse, along with a suite of other innovations — including the chorded keyboard and collaborative computing tools — in his legendary 1968 demonstration, now known as The Mother of All Demos. One must keep in mind that most computers at the time were used via batch processing—users submitted jobs to operators and received results hours or days later. Real-time interaction, as Engelbart demonstrated, was nearly unthinkable.

Life after the Demo

Despite the monumental impact of the 1968 “Mother of All Demos,” Engelbart's influence began to fade surprisingly quickly. By the mid-1970s, he had slipped into relative obscurity, and his lab—the Augmentation Research Center—began to unravel. Several of his researchers left for Xerox PARC, frustrated by internal tensions and differing visions for the future of computing.

While Engelbart believed in collaborative, networked systems—computers as shared tools for solving complex problems—many younger engineers were drawn to the emerging idea of personal computing, decentralized and individualized.

This wasn’t just a technical disagreement—it was ideological. Engelbart’s work still carried the logic of time-sharing and central coordination, while his successors at Xerox PARC and, later, Apple, would popularize a vision of computing as personal, private, and untethered.

In 1976, the remnants of his lab were transferred to Tymshare, a commercial computing firm. Engelbart joined as a Senior Scientist, and NLS was renamed Augment and marketed as an office automation tool. But his desire to continue research was stifled by corporate priorities.

Later, when Tymshare was acquired by McDonnell Douglas in the 1980s, he attempted to align his work with the company’s aerospace needs—arguing that complex engineering projects demanded better knowledge management systems. While a few executives showed interest, real support never materialized.

After retiring in 1986, Engelbart returned to his core mission: improving how humans collaborate and solve hard problems. In 1988, alongside his daughter Christina Engelbart, he founded the Bootstrap Institute (now the Doug Engelbart Institute). Their work centered on “Collective IQ” — the idea that technology should be used not just for productivity, but to amplify our collective capacity to think, solve, and innovate together.

Through seminars, consulting, and small-scale collaborations, Engelbart spent the final decades of his life championing ideas that had always been ahead of their time. In the mid-1990s, he received some DARPA funding to develop a modern interface for Augment, and in 2005, the HyperScope project aimed to bring his hyperlinked document vision into the browser era.

Suggested reading:

- “Bookstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing,” by Thierry Bardini (2000)

- "How Douglas Engelbart Invented the Future" - Smithsonian magazine article